Cigarbutt

Member-

Posts

3,373 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Everything posted by Cigarbutt

-

^After wabuffo, i would say Mr. Pozsar is the person to turn to for an interesting and valuable perspective about these matters. His notes are short and he uses helpful analogies (ie toilet tank mechanism analogy). His perspective was helpful when there was a repo 'crisis' in September 2019 (repo rates were shooting higher then, when it was realized that there was a level of excess reserves that was not, in fact, excessive, under present regulatory and capital restraints). So much for tightening and the i- could-stop-any-time-i-like mentality. His most recent take (and short term technical outlook vs debt ceiling discussions and all) is included here: https://plus.credit-suisse.com/rpc4/ravDocView?docid=V7r9LA2AN-Vvd1 Mr. Pozsar describes a situation where basically all the cash that was 'spent' from the account held by the Treasury at the Fed has been rotated to the RRP facility (through money market funds). He expects the RRP to continue to build up. It appears that the Treasury will aim for about 450B in the account for the summer transition, a level higher than prescribed but apparently justified because of 'extraordinary' circumstances. If you think it's possible to determine if the level of traffic at the Times Square intersection is a good indicator of the New York economy, then you may think that it's helpful to look into issues related to the central financial plumbing but it's mostly technical stuff, a topic for which Mr. Pozsar's provides a useful perspective. The underlying fundamental assumption though is that market participants will cooperate in good times and collaborate in less good times. The momentum trend for now is for the Fed to continue to provide, ad hoc, more temporary technical adjustments that tend to get larger over time (as a % of the real private economy) and that tend to become permanent.

-

Mr. Weschler, in his response to the ProPublica 'investigation', summarized well a reasonable and balanced way to improve the equity outcome for all, concerning this specific aspect (intent of the underlying legislation): "In closing, although I have been an enormous beneficiary of the IRA mechanism, I personally do not feel the tax shield afforded me by my IRA is necessarily good tax policy. To this end, I am openly supportive of modifying the benefit afforded to retirement accounts once they exceed a certain threshold." For the Roth-IRA equivalent in Canada (TFSAs), there is no effective cap but the CRA (IRS-equivalent) appears to be more pro-active (for better or for worse) and they seem to base their audit efforts and legal actions on $ thresholds. Based on a few relevant inputs, once in the audit phase, the CRA looks at the composition of the portfolio, at the frequency of 'trading' and a good defense is to show investment-based decisions in tax-deferred accounts that are proportional to what happens in non tax-deferred accounts. Rules could be clarified though instead of waiting for case law to develop and retroactive changes raise fairness issues as well. A simple cap or a simple cap-equivalent seem to be the most effective way to deal with this. In Canada, the tax-deferred education funds (RESPs) do not have hard caps but have effective functional caps because of the finite life of the programs. If you end up with excess funds (more money than was necessary to pay for higher education), you have three choices: 1-use available room elsewhere to move the funds to another form of registered tax-deferred accounts (based on available contribution limits per year so no compounding possible), 2-transfer the excess funds to an education institution as a donation (not tax deductible) or 3- retire the funds as ordinary income taxed at 70 to 75%. The rules are somewhat cumbersome overall and you have to think like a defined benefit pension plan with fairly unknown assumptions but i think most dedicated participants 'get' it.

-

@LongHaul i'm happy to hear that. i understand that you show a healthy suspicion (disdain?) of experts. i also saw this interview on CNN: https://www.cnn.com/videos/tv/2021/05/21/amanpour-kahneman-noise.cnn This is early Sunday morning and here are a few additional points (some of which investment and noise related (and some not) and it may interest you? Recently (i got this through a Morninstar article), i spent about 5 minutes on a study (if it interests you, i could give you a link but i wouldn't bother since the study has significant limitations) which is relevant to the link between noise and investment decisions. The study was made in Taiwan (where retail investing is very significant) and the authors were able to show an increased level of buying activity in momentum stocks (through local brokerage houses) in the days following a specific event which was the occurrence of the public announcement of a local lottery win. It's possible that "feeling lucky" makes one feel like a real winner. This seems like a slippery and noisy slope. Some time ago, you mentioned a book which i had read before and which i did not find particularly useful but the topic is fascinating: Fear. And there may be a link about noise. Fear can be noisy (and ridiculed) but it's an emotion wired deep within our brain that has contributed to the survival of the species. For somebody heavily 'biased' to rational thinking, how do you decrease noise but preserve the basic fear instinct that can be fundamentally useful (even for survival, financial or otherwise). When in training in the 80s, it was required to go through a few weeks of psychiatry in the real world. As you may know, psychiatry is a very noisy specialty, a weakness which has been very partially addressed by devising a series of committee-type "DSM" diagnostic manuals with lists of specific criteria. The real difficulty is that those underlying criteria (fatigue etc) are very subjective. By combining very specific criteria into a constellation of symptoms, the noise is reduced, at least partly. The main lesson that i got from this experience was how to integrate fear into the algorithm concerning a specific situation. There was a rule that, when alone with a psychiatry patient (psychiatry patients can be, at times, dangerous), one had to sit between the door and the patient (to be able to flee or call for help in the event of threat). There's been some work to quantify fear or to find alternative and more objective measures of fear (including AI stuff) but this is an area where fundamental human intuition cannot be replaced. The best, by far, indicator of fear (as a threat to one's security or survival) is an intrinsic feeling that is difficult to describe but that is also unmistakable (if you're appropriately alert to it). When deeply felt, at least keep a clear path to the door (or the exit). It's the same with the fear and greed thing and capital markets that Mr. Buffett describes. Edit (final comment): This is an area where you may want to have a higher relative rate of false positives (margin of safety) but, obviously, that's an individual responsibility and the decision outcome may be correlated to the level of one's predisposition in "feeling lucky".

-

^Since the early 2002-4 hard market, i've used MarketScout and have found the tool useful for a general idea of the coincident market. For example, in 2002-4, it helped to map out what kind of growth (from the point of view of both price and number of policies) in NPW FFH would report. Market Barometers – MarketScout They think the hard market is moderating. ----- Even if these measures are coincident and relevant, they still don't provide clear answers about the softness of the past (Mr. Stephen Catlin whose opinion needs to be respected, for example, suspects that a lot of swimmers have been naked (in some significant areas) and that the tide has not quite receded yet) and about the surprises of the future. ----- An area of the market which may reflect the unusual risk appetite arising as a side effect of 0% interest rates is the catastrophe bond market (and the rest of the ILS market). Catastrophe bond hard market continued to weaken in Q2: Lane Financial - Artemis.bm The rates obtained likely point to relatively low returns going forward and leave little margin of safety (it's the insurance industry after all and we're talking catastrophes). ----- Conclusion: this is not shaping up to be the mother of all hard markets.

-

@Munger_Disciple Here's more reasoned content then: ---) Your conclusion is wrong. -i started out (the investing thing) wanting to have core holdings (index-like) and a few marginal relative winners and ended up (because of intrinsic and extrinsic circumstances, most of which outside my control) being unusually contrarian, concentrated and opportunistic which makes my participation useless at least 99% of the times here but i'm trying to improve. -i think this site should move more towards a VIC-style (focus on individual names, impersonal and factual analysis etc) of content but then you'd lose the meeting place aspect. It's a tough act to balance. -i tend to be a real jerk in real life but, contrary to most, anonymous participation in on-line discussions has a moderating effect on me. i've discovered that i even enjoy discussions in forums (elsewhere) where inputs are superficial in content, low in analytical power and littered with inappropriate statements. Humans are fascinating. -There is a topic (relevant to bubbles, macro and individual names) i've been working on and i may share some of the conclusions. ----) Back to: Are we in (one of the most interesting periods in history for investing) a bubble?

-

OK, maybe. Let's try again. 1-Treasury deficit spending increases private net worth. 2-Treasury deficit spending does not increase total net worth. It seems both 1- and 2- can be reconciled but (IMO) that's not the key underlying question. The Treasury-acting-like-a-financial-intermediate analogy was to underline the role in central financial intermediation (both now and across time periods). The Treasury-Fed financial complex has engineered a massive balance sheet expansion movement (Fed balance sheet, but also big banks balance sheet and the systemic balance sheet). There is just so much more government debt and offsetting cash floating around. The excess cash within the system may move around but will not magically disappear or transform into wealth. The excess cash will disappear only when the underlying debt will be retired. There is nothing wrong per se with balance sheet expansion but one has to try to see what it means under present circumstances. The key is what the debt (and offsetting cash) is used for. With all this bu**le talk going on now, it seems that ultra-low interest rates have been a determinant factor in the recent evolution in the growth of money supply versus underlying economic growth (and the related change in the ratio of base money and loans backing deposits at large commercial banks) and this trend (which accelerated lately) has been firmly in place since the GFC. It has been said that ultra-low interest rates may represent a sign of financial and societal sophistication but the contrarian side in me suggests that it could represent a sign of stupidity, especially the managed part. Of course, it could be somewhere in between and that's what i'm trying to figure out. BTW, i really appreciate reading your thoughts because it allows me to see perspectives that are not within my basic mental models. i understand that this is likely not proportionally reciprocal and this may represent my habit of choosing stronger opponents. CF

-

Today, we're making home-made strawberry jam and it feels like some of us have a similar argument: Some say, there is too much sugar in the jam. Others suggest that the amount of sugar in the house has not changed. And maybe both are right. Some of the confusion may be related to the fact that we're trying to combine income statement and balance sheet elements in the same statement. Let's see if the following concept helps. In typical times, most or all of the Treasury spending (to the private sector) is matched by taxation revenue (from the private sector). The rest applies to deficit spending. When the Treasury spends money it does not have, it behaves like a bank (sort of) that act as an intermediate between a private actor that lends its cash (instead of consuming, investing or whatever) to another private actor (to consume, invest or whatever) through the Treasury. So the Treasury acting like a bank (sort of) can effectively be involved in money creation, through some kind of loan-deposit cycle, with a difference that the Treasury holds the expanded balance sheet in an inter-temporal way. i would say the Fed has exploited this temporal loophole while the MMT crowd simply want to never have to deal with it. The Rubicon hasn't been crossed but.. The concept is imperfect but helps to explain the notion that the country owns the growing debt to itself (with no change in consolidated net worth with rising deficits), forgetting the current account part and forgetting that the debt assets are not distributed like the debt liabilities. Speaking of inter-temporal tricks and the upcoming noise around the debt ceiling (preventing private sector net worth growth ), you may enjoy this video which i thought funny (in 2011).

-

i would say this line of thinking (move out of bonds, shift to equities) could be misleading. When you sell your bond to me (for example), the bond is not retired and continues to exist; money cannot leave a sector if that sector still exists and the bond market has been growing ++. After (not quite maybe) the most impressive bond bull market ever, there's still huge demand for bonds (people wanting to enter to take the place of those who want to leave), including for government debt securities. Have you recently looked at too-big-to-fail banks and their bulging holdings (assets) of government debt? This is also apparent in the recent demand that was high in the reverse repo market (cash being exchanged for low duration government debt) with a yield of 0%, a demand that skyrocketed to 772.6B (it was basically at zero last March) when yields offered by the Fed 'jumped' to 0.05%. So, the underlying question is: where is all this (new) money coming from? Apart from the usual money creation from loan growth at banking institutions (which has been less than impressive lately (ask JPM, BoA etc), the government has put its shoulder to the wheel but government issues are not pure money printing, at least for now, as the cash injected into the system has been offset by government bonds held (ultimately) by someone. So, the unusual increase in the money (cash) supply has been offset by an equivalent increase in the total pool of bond securities, so resulting in a higher supply of bonds met with an even larger demand for such securities (driving the price up) and resulting in ultra-low yields (30-yr risk-free at 1.97-2.04% today). So, the recent story has been a large increase in the size of the bond market offset by an increase of cash. Some of this cash went to money market funds (searching for yields at the zero bound) and some of the cash ended up in deposits, contributing to a record opening of brokerage accounts in the first half of 2021 with the purpose to replace owners of volatile stocks. ----- The 580B inflow number into global equity funds for Q1Q2 2021 looks impressive and is quite unusual but global equity market cap (from a few sources although i did not check in details) is now above 100T. Reading Dalbar studies about retail investors (and inferior returns) is interesting for hindsight perspective but it's always possible that the retail crowd is seeing something that smart money isn't. Of course, i wouldn't bet on it.

-

OK, so i like John Deere, Disney and Costco (like in the sense of long duration assets) and wonder what discount rate to use for the ultimate cashflows that will be delivered over time during the ownership period. The 'relation' between interest rates and valuation is kind of obvious, on a first level basis, but are there not potential problems (risks)? The relation between interest rates and valuations have not been consistent over time and over different geographies (of course framing the question using certain specific time frames can do the trick). See: Stock-Inflation-and-PE.pdf (crestmontresearch.com) We know 10-year rates are tied to longer-term inflation rates at the hip and the 10-yr rate to CAPE correlation (for example) has been anything but consistent ie no obvious correlation over very long periods and, in fact, showed a completely non-intuitive strong and positive correlation between 1949-1968 (19 years!; a period during which certain partnerships did really well): In the spirit of necessary adjustments, the effective corporate tax rate was essentially the same at beginning and end of period and the US government did not produce fiscal surplus to kill the economy or something during the period (the US decreased public debt from 110% to 30% of GDP then due to productivity gains and real growth). This post is because i read these days (here and elsewhere) that low interest rates justify higher valuations and i wonder. If one follows the reasoning, if interest rates (like the 10-yr rate; scenario not as far-fetched as some may suggest) get divided by 2 or even 3, we could make the Japan stock and real estate market, 1989 edition, appear justified (that's what many people said then contemporaneously). The point is that today's valuations may make sense from a fundamental point of view but it is a stretch to suggest that low interest rates justify today's valuations. Of course, the relevant question is not the rear-view mirror question. Opinion: it's likely that, in the future, the conclusion will be that, low interest rates, by themselves, do not justify valuations. Not everyone agrees and that's fine.

-

You are asking about sentiment so who knows especially in terms of timing. FWIW, During the dot-com build-up, i was fresh out of university and forming some kind of self-directed investment framework. One of the holdings was BCE.TO (telecom giant) and it spun off Nortel shares (star dot-com darling in Canada) which i kept for a while. i sold Nortel before seeing it triple. The selling was not because i saw the bu**le (although i had read the Buffett 1999 general valuation article), it was because i was not able to understand Nortel’s business. Being not able to understand became a recurrent theme afterwards. In social meetings (as a proxy for sentiment) with ‘friends’ in the extended circle (many graduates including in the technology and computer science fields), ‘investing’ was a prominent topic during the rise but became a taboo topic thereafter. Anyways, disclosing that i had sold Nortel disqualified me to the 'investing' discussions. During that time and up to 2001-2, I was getting ready to invest in Fairfax Financial and to get an idea about the technology bubble sentiment then, reading the ‘investments’ section in Mr. Watsa’s introductory letters (1999, 2000 and 2001) may not be a poor investment of your time. The times, they are changin’ but human nature.. Who am i to say but, whatever you do, it’s probably a good idea to have a long term outlook. That period is also when i opened a self-directed higher education fund for my kids (both born and to come) and this also required hope for the future.

-

It’s a good book! The “noise” topic has been discussed by Mr. Kahneman and others before but the book is an actualized summary, kind of. Here’s a summary and review which i’ve tried real hard to make bias- and noise-free. The topic (decision making and communication) has always been a parallel interest wherever most of my time has been spent (professional and personal). FWIW. The topic is tangentially relevant to an investment board because of the behavioral finance aspect. The main author is well known and the co-authors are O. Sibony, an ‘academic’ business consultant and C. Sunstein, an ‘academic’ behavioral specialist with some ‘political’ experience (under the Obama administration). They explain that noise is not bias. Biases are many (‘social’ and cognitive) but their defining characteristic is that they tend to cause decisions to be wrong in a consistent and systematic way. Biases are well known and are easy to recognize (especially in others..). The book is not about biases although the difference between noise and bias, contrary to what the authors seem to suggest, is not completely binary but more along a spectrum especially for some types of noise (see paragraphs below). Helpful picture from previous relevant publication to illustrate difference between noise and bias: Their definition of noise is basically unwanted variability in judgments or decision making outcomes not explained by biases. The backbone of the book is to show real-life examples where noise is a source of poor decision outcomes in many fields: medical, legal, business valuations and appraisals, economic forecasts etc. They define two basic types (or sources) of noise and suggest potential solutions to measure noise, reduce it and improve decision making. The basic message is that inconsistency in judgements has a lot to do with noise and they try to show ways to introduce some kind of discipline in the wildness. The most basic form (and the most amenable to improvement) of noise is the variability due to general circumstances unrelated and irrelevant to the actual decision process (ie mood, weather, fatigue, unrelated circumstances of daily life). This type of noise explains the significant intra-observer variability (same person evaluating same data at different times) that has been documented in many areas. This seems like a rather mundane concern but it’s a huge problem in many important domains. It’s been shown that sentencing and other various decisions with legal implications can be influenced significantly by completely unrelated and irrelevant factors. The other forms of noise, which can be joined into one group, reflect a general tendency for individuals to lean certain ways and/or to think differently (different thought process or different patterns of assessment). There is a potential intersection with bias here but it’s important to make a distinction when trying to measure and address this sub-type of noise because the strategies are different. This noise, even if it originates from individual variations and even if this noise has bias-like characteristics at the individual level, is really noise that can be impactful at the systemic level. {Personal note: in some cases (administrative courts and others) where i’ve been involved as an ‘expert’, the two opposing parties would learn who the judge was sitting the morning of the audience and, in in significant number of cases, this would trigger some kind of settlement or even dropping the case because of the extreme ways some judges were consistently leaning (typically a right-left thing or a variation thereof) which underlined the excessive variability embedded in the process (it felt almost like a lottery at times)}. For example, the authors describe how physicians come to different conclusions (diagnosis) when assessing the same patient or the same set of data. This is also striking in sub-groups where objectivity of data is more prominent in the decision process (ie analysis of pathology specimens under the microscope, imaging studies evaluated by radiologists) where one would not expect such variability. In fact, when relevant participants learn about such variability levels, they are surprised and are expecting much less variations. You have both inter-observer variability and intra-observer variability. The intra-observer variability is clearly and essentially unwanted noise, especially when the variability is large and impactful (it often is). They describe similar scenarios in the legal field and in the process of various business appraisals including underwriting decisions. Some of this noise is related to uncertainty of the underlying problem or issue but a significant part of this noise is detrimental and unwanted. A key aspect that is only touched upon in the book is the importance of not completely eliminating noise because, when looking at this from a systemic level, one has to strike a reasonable balance between the asset of the potential to be right unconventionally (atypical but possible) and the liability of being wrong unconventionally (typical). In fact, one could argue that, as an individual, to be a successful contrarian investor requires to succeed unconventionally but the book is not a recipe to beat the market, it’s a guide to improve systematic decision making and it seems clear that noise levels are very high in various areas of decision making and the systematic cost of this noise is also very high. There can be tremendous value in intuitive judgements, especially in certain situations, but the noise associated with intuitions can be very large and damaging. Intuition is one of the driving forces behind « animal spirits ». Animal spirits should not be killed but they have to be kept in check. {People who follow the opioid crisis saga may be interested to look into what a specific judge is trying to do in an Ohio court. The judge has taken an intuitive (and potentially noisy) route and is meeting checks and balances. The GSEs’ potential to leave conservatorship and the legal implications also reveal noise-related issues as well as the issue of different and opposing schools of thought and various levels of decision powers (legislative versus judicial).} The first step is to accept that noise exists, can be measured and remediated. The authors define how noise can be measured (‘noise audit’) and describe various ‘hygienic’ decision (noise reduction) techniques. They also address some cost-benefit considerations before undertaking such projects. Although not explicitly mentioned in the book, simply seriously considering the noise effect and its consequences on the decision-making process (similar to the Hawthorne effect) can be associated with improved outcomes, although this may be temporary in nature. But constructive attempts to improve the culture can result in lasting and self-sustaining improvements. The authors give concrete examples and suggest to focus on areas where unwanted variability is high and where standardization of the process and introduction of objective criteria even if underlying variables are subjective in nature, can effectively reduce noise with acceptable costs (financial costs, productivity issues etc). They give the basic example of hand washing. Hand washing, in certain selected circumstances has been shown to reduce bad outcomes. By making the hand washing component automatic or as part of a standard routine, some noise tends to be automatically eliminated form the decision making process and outcomes are improved. People have understood this for a long time in the aviation industry (safety aspect), importance of protocols, checklists etc. {In my humble experience, apparently small and simple (but well designed) improvements can result in immediate, impressive and sustainable improvements.} They also suggest the possibility to aggregate more than one decision maker when unusually impactful decisions are made. This is applied in top management candidate selection and in higher education contingent candidate selection. You can see this aspect operating at the Board of Directors level, especially if decisions (such are mergers) are separated into sub-units and evaluated independently. This is controversial and may not work because of the potential echo-chamber effect and others and because of the risk to miss the forest from the trees. {This is the idea behind the structure of Supreme Courts. Anecdotally, i've been involved in individual peer reviews that could (and sometimes did) significantly curtail their professional activities and i've found that independent reviews coalesced into a 'committee' tends to work best under these circumstances, partly to reduce noise.} They contend that intuitions and hunches have to be controlled somehow but, even if conceptually attractive, this is often hard to achieve in real life, especially when human factors are critical such as during a negotiating process or when biases play a major factor. A promising area is the introduction of algorithms (potentially AI or AI-like) to be used alongside the decision making process. Whatever is attempted, ease of use and practicality are required for acceptance by market participants. Also, poorly designed guidelines or algorithms can be sources of additional noise (and bias). -Additional personal and anecdotal comments of questionable significance {When i started out in practice about 25 years ago, after a few weeks, i noticed a very high rate of inadequate relevance of consultations referred to me for various reasons and this was supported by various (poorly designed) incentives. For many reasons, changing incentives was the fundamental thing to do but that’s complicated and attempts are often met with great resistance. This resulted in a lot of noise and poor outcomes mostly because of poor resource allocation (quantity, quality and timing). After a few relatively simple steps (and engaging with others with skin in the game), all consultations in my area (about 500k population) became essentially channeled into a centralized process with a unique reception area where consultation requests were assessed using simple and objective criteria and using a simple and standardized form that reflected current standards of practice with the possibility (not the default option) to go around the standard procedure. This simple process resulted in a significant reduction of noise with a marked improvement in timely resource allocation. Over the years, many similar projects followed using various protocols for example in dealing with frequently seen clinical presentations. It became obvious that noise can be reduced and it typically ends up as a win-win for all (or at least most) involved. Later on, i also became involved in the legal arena (independent expert reports, independent decisions) and it became obvious that noise was a significant problem. By using standardized criteria, formation and training to reach the ‘expert’ level admissibility, by standardizing the evaluation/decision process and by listing requirements expected in formal reports, noise level was significantly reduced. For example, it’s being recognized that expert reports as well as decisions and case law based on specific criteria (motivated by facts and reasoning, rules based) have more weight than work produced more on the basis of vague principles or even impressions. A recent review completed in a specific segment (that was felt to be problematic) simply verifying the basic features considered required in an ‘expert’ report resulted in an assessment whereby about a third of the reports had no value and another third had little value. Authors of such reports have been notified (improve the noise or do something else).} ----- The authors show that, in some areas, including some critical areas, noise level is excessive and has consequences. This can be improved. In some specific areas, decentralized hunches and superficial impressions do a lot more harm than good and checks and balances are required in order to improve the decision-making process. ----- **Clearly an optional section here, simply skip if your worldview is threatened by it. -Comments about the coronavirus episode This is now considered a twilight zone topic here and some may have a point about relevance to investments. That’s fine. The elephant in the room though is not the relevance or even the ‘political’ aspect, it’s the situation where achieving levels of constructive on-line conversations can be challenging when the style becomes dominated by noisy and biased tribal thinking and by inappropriate components that destroy engagement. AFAIK, the book was not intended to be applied to the Covid-19 issue and the main author has only superficially associated the two in related interviews. From limited information, it appears that Mr. Kahneman thinks that a lot of noise happened as a result of the pandemic but he seems to suggest that biases played a much more important role. The noise played out mostly in relation to a growing diversity of alternative assessment styles and polarization of thought processes. That's all i'm goin' to say about that. For those interested, Mr. Micheal Lewis has recently released an interesting book about the pandemic called The Premonition. The noise concept is not the primary theme but the author, through a few ‘stories’, tries to explain gaps between reputation, capacity and actual performance and how talents can be wasted when leadership fails. Mr. Lewis also touches upon the possibility, related to growing noise in the public environment, that 2020-1 showed a deeper developing fissure than simply the controversial place of ‘science’ in public life. **End of optional section ----- It’s interesting to compare this recent book to the work Mr. Kahneman produced a long time ago (1970s) on the value and risks of intuitions and how he has evolved with a refined definition for noise, away from biases. Overall, a good book if noise is your thing and if you have enjoyed Kahneman and Tversky’s previous works.

-

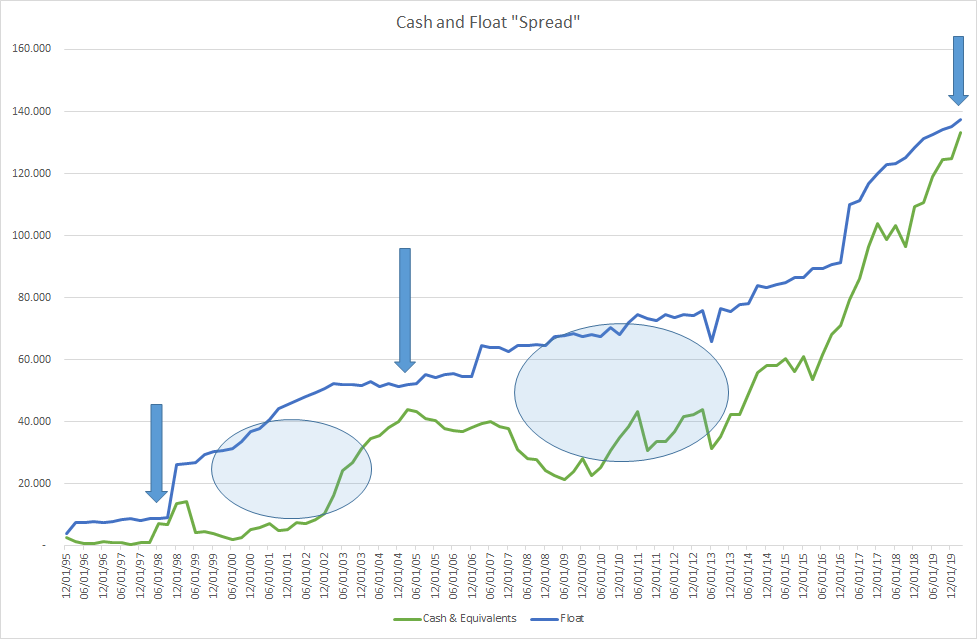

^Slightly different opinion on the position of the portfolio now versus 5, 10 or 20 years ago and the inflation question. First, Mr. Buffett has maintained (whatever the explanation or cause) a more or less 100% coverage of cash and fixed income over float with slightly lower float coverage with cash and fixed income when there were not as many reasons to hate cash. Even if the float portfolio was always protected against inflation and the potential effect on fixed income instruments, there has been a radical change in the relative size of the fixed income portfolio and in its composition and one may suggest that it is extra-protected at this point. Comparing with other insurers makes this almost six-sigma difference now even more apparent. A nice feature of the present "position" is that the incredibly-low duration cash and fixed income portfolio could reveal its optionality value in pretty much any circumstance or environment, if that's considered something of value, at a minimum to help with deep sleep. During 1998 and 1999, BRK was digesting GenRe and numbers moved around a bit but the integration did not really change the conclusion here as a similar "pattern" in asset allocation was reported in the following years (1999 to 2002). In 1998, float was 22.8B, fixed income was 21.2B and cash+CE was 13.6B. Fixed income over float was 0.93 In 1998, the cash/FI over float was unusually high and cash went down by 9.8B in 1999. Of the FI 21.2B, 30% was 5-10 years, 30% was more than 10 years and 6% were MBS. Also, 12.2B were US gov.-related and 4.6 were corporates. In Q1 2021, float was about 140B, fixed income was at 20.0B and cash+CE was around 145B. Fixed income over float was 0.14. Cash/FI over float is again relatively high (similar to 1997-9 and 2004-6 and that's all i'm goin' to say about that). Of the FI 20.0B, 9.8B was less than 1 year, 8.8B was between 1 and 5 years. End of 2020 numbers reported about interest rate risk reveal immaterial changes and extremely low duration. Also, 3.2B were US gov.-related, 12.1 were highly graded foreign gov.-related and 4.2 were corporates. While float has been multiplied by more than 6x, exposure to longer term debt has remained essentially the same (in absolute numbers) and duration is down, significantly, even if relatively low to start with. Corporate debt exposure is also down (absolutely and relatively++). The following graph borrowed from a Seeking Alpha article sort of says something similar with the distance between the cash line and the float line being the fixed income exposure. It seems that cash levels, for the first time in history, has taken over the float line but that's another story.

-

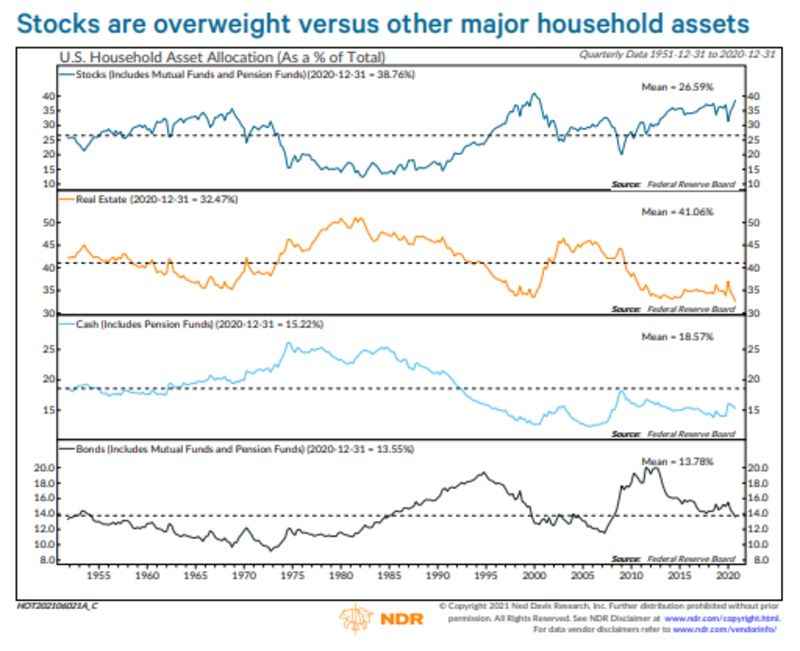

@Munger_Disciple i don't really want to enter the debate (Inflation/deflation yada yada) but here's some potentially useful info. The CPI is based on 8 groups, 2 of which are education (and communication) and medical care. For wages, i've used the following and found it to be reliable: Wage Growth Tracker - Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta (atlantafed.org) For housing, there are two aspects: consumer aspect and investment aspect. In the last 30 years or so, the investment aspect has become much more predominant (and more recently, in a more volatile way). So you have consumer inflation and asset inflation. As an individual (or a household), i guess you want a low housing consumer inflation aspect and high housing asset inflation aspect... Anyways, your consumer inflation may be different (perhaps very significantly) from others and the CPI "measure" could be improved but it may be a useful starting point for a reflection. Anecdotally (and in a very irrelevant way), in the last few years, the consumer inflation that my household has been exposed to (consumer products, employees etc) has been very mild although we tend to notice when prices "jump" at times. @LearningMachine i don't really want to enter this debate among great minds but the cash-on-the-sideline thing is a tricky concept. Let's say i use my cash on the sideline to buy your VZ shares, then you have cash on the sideline. Even if i use margin cash, then i use cash on the sideline from someone else. The noise about all this growth in cash deposits is simply a reflection of expanding balance sheets (commercial banks, the Fed etc). For example, during 2020-1, corporates have built cash (for which they now face negative rates when they try to deposit at JPM or BAC) but the increase in cash was matched by revolver draws and debt issuance. Without entering the irrelevant question about the possible presence of systemic excess cash or excess debt, it's interesting to note that, during 2020-1, money market funds AUM increased by about 1T, of which all was channeled into short term government debt yielding essentially 0%. And since mid-March 2021, when MMFs call JPM and BAC, they are offered negative rates so they have turned to the reverse repo market and bought more than 500B of short-term repo collateral (short term government debt) in exchange for cash and a 0% (or slightly negative yield). i guess the opportunity cost is about 0% for cash on the sideline. Anyways, whatever your perspective on this wave of liquidity waiting to stir animal spirits, you have to reconcile with the following recent asset allocation profile prepared by Ned Davis (excellent data). Some conclusions from the graphs appear counter-intuitive but it's not fake news and it all makes sense if you actually go through the numbers.

-

Saying everyone’s wrong comes with the very real risk of being irrelevant. A last irrelevant bit, for a while: The best part (IMO), which lasts one or two seconds, of The Big Short is at 2:09 of this clip. That fleeting smile. It seems that being able to feel what Dr. Burry is feeling then may mean that there is some understanding and perhaps less of a disconnect than the main character displays overall with his environment. The Big Short (2015) - Dr. Michael Burry Betting Against the Housing Market [HD 1080p] - YouTube And he’s not always wrong.

-

This should be a pretty boring aspect of the 'market' but with all this inflation-is-here-and-everywhere perception and the building tension between fiat and crypto currencies, what is happening these days in the reverse repo market is quite unusual (and fascinating). Mainstream does not seem to care as well as the informed investment community. For the reserves aspect, the Fed continues to be involved in the secondary market by buying securities (and supplying reserves) while, at the same time, removing reserves through the RRP. What is going on here? Since the end of March, very little net reserves have been added to the financial plumbing, on a net basis, even if the TGA has been steadily decreasing (minus 261.2B since March 31st to May 19th). The easy technical thing to do, to let reserves build within the system, would have been to continue the SLR exemption for banks. The Fed decided otherwise for the time being and instead put in place conditions where banks are 'encouraged' to shed reserves to money market funds who themselves are trying to find places to park cash (i realize that repo people don't like the notion of money parking and see this instead as a leveraged profit opportunity) and 0% (and even negative rates at times!) happen to be the best relative opportunity. The problem is that MMFs are likely close to their limit in terms of reverse repo exposure. What happens next? Data (context of of an impression that wild inflation is coming): Treasury yields: 3mo:0.00 6mo:0.01 12mo:0.04 Even the 10-yr is at 1.62%. The graph above shows the reverse repo action. Before January 2018, the banks used to like the RRP action especially for window dressing at the end of quarters. Since Basel III, the space has become too expensive (regulatory costs). Apart from a blip with the March financial plumbing liquidity issue in March 2020. Lately, the MMFs have been 'encouraged to participate and (sometimes) to pay in order to lend cash? There is so much cash and so many risk-free securities sloshing around and i hope the Fed notice the unstable stability but that may be too much to ask. The following is an interesting discussion: American SICO - 4.1 A Band-Aid Known as Reverse Repo (fed.tips) The title is American Sico (Psycho) and i absolutely and relatively loved that movie. So much potential energy waiting to be released.

-

Cancelation of Homeowners Policies in Florida

Cigarbutt replied to DooDiligence's topic in General Discussion

^The Florida P+C re/insurance market has entered the vicinity of a perfect storm (!) as clouds have been gathering in the last few years. Many forces at work, some natural, others man-made and some 'collectively' self-inflicted. The following Miami Herald article may help to digest the cancellation as the growing problem seems to be widespread. Three more insurance carriers canceling Florida policies | Miami Herald There are reasonable criteria allowing individuals and insurers to unilaterally cancel contracts and financial hardship is one of them but some unduly take advantage of the flexible definition of a contract. Many factors at work and building up over a long time but litigation issues seem to be significant (there are so many embedded poor incentives at all levels with the insurer squeezed in the middle). Premium rates are expected to rise (perhaps much more if nature refuses to cooperate) and stabilization is to be expected when public funds will retain less and outside parties like BRK come in (similar to 2008) to submit reinsurance bids. It looks like 75% of the reinsurance money covering property losses in Florida comes from investors out of state. Florida Citizens to seek $850m of cat bonds before 2021 hurricane season - Artemis.bm Rising combined ratios, lower capital, to drive Florida reinsurance demand - Artemis.bm Industry flags litigation as biggest issue facing Florida's re/insurance market - Reinsurance News Disclosure: i like Florida for many reasons and may spend part of winters there when my perimeter becomes more limited. -

^If interested, Enova (ENVA), which is a relevant 'fintech' loan intermediate comparable, integrated the fair value rule for loans receivables starting Jan 1st 2020. Their 2019 supplemental financial information found in their investor relations' section shows an interesting pro-forma picture (page 11). There is also an August 2020 presentation that can be found by Google (no longer on their website it seems) which has two pages on the issue (pages 38-39), rationale, accounting effect etc. Interestingly, ENVA recently announced that their annual meeting was being postponed in relation to an auditor selection.. -----) Back to a great time to be alive and $$FGNA$$

-

One question that keeps coming back when going over this approach (cognitive approach, for biases etc) is how people who are receptive to this approach may, in fact, be predisposed to these approaches because of pre-established predispositions (genetic and upbringing). What i mean is, for example, that people who come to read (and apply) Dale Carnegie's How to Win Friends and Influence People may have already built-in predispositions to make friends and influence people to start with, ie the outcome is highly correlated to the cognitive starting point already imprinted. This has been shown in more extreme cases when trying to influence criminal behaviors once 'patterns' are established. Anyways, thank you for the idea. i read through the book very rapidly. Since the last edition of this book, the controversy between more 'biological' approaches and cognitive approaches lives on and antidepressant use in the US has almost doubled.

-

^Not much protection left, if any IMO. -A big chunk of the CPI-linked derivative notional value will go with the European run-off. -Overall, they've had a tendency to let contracts mature. -The residual duration was at 2.7 years at 2020 yr-end. -The contracts are far out of the money and a 5 to 10% deflation would be required to make the trade profitable upon maturation. -Even if potentially of value as a trading vehicle, the short period to maturation lessens the potential convexity to a significant degree. Anyways all the above points may be irrelevant. When those contracts were initiated, some people put in opposition the deflation thesis with an opposing view (championed by Mr. Buffett for example) that deficit spending could counteract deflationary forces and recent events suggest that this possibility remains alive and well. ---) Back to FFH and investing.

-

^About the bond investing bucket for FFH. It's an important part because the bond portfolio could very well match shareholders' equity and more. As SJ describes, the bond portfolio can be seen from many angles (source of earnings, pool of funds to pay claims, and a potential for positive returns in a contrarian way). Investing in FFH in the early 2000s meant expectations of superior returns on the bond portfolio going forward. As reported in 2004 (first time reported in this form): Bonds 12.0% 9.8% 9.8% Merrill Lynch Corporate Index 8.0% 7.9% 7.9% for 5, 10 and 15 year periods. As reported in 2016 (last reported in this form in 2017 and 2016 matches with a shift in personal opinion vs expected future excess returns on bond portfolio; 2017 reported numbers similar (slightly lower overall) vs 2016): Taxable bonds 6.0% 9.6% 10.3% Merrill Lynch U.S. corporate (1-10 year) bond index 3.8% 4.9% 5.1% for 5, 10 and 15 year periods. The bond results don't include the CDS returns. So, investment results from bonds (period 2001 to 2016) had been significant contributors to the bottom line. This hasn't been much discussed but the bond performance since 2016 (year when expectations about inflation changed, at least as reported) has been less impressive, see 10-yr Treasury constant rate graph for reference (what happened since 2016, where we are now after the Covid-19 episode etc). i submit the opinion that the present bond environment is, by far, most challenging (ever?). Also, during 2020, the Fed (and Treasury) put in place backstops (for corporate bonds and munis) that were relatively symbolic but that crystallized the notion (similar for GSEs and the implicit support concept) that such backstops and more will happen again anytime stress appears in the credit markets and what happens if there is a Lehman moment or a bond equivalent? At this point, FFH is positioned with low duration and liquidity but they don't have residual protection against a deflationary environment. What happens next in the bond markets is anybody's guess but reading again parts of the earlier annual reports helps to remember how FFH used to be able to find relatively cheap ways to benefit if real risk shows its ugly head. 10-year.pdf yields-overview.pdf

-

Than you for this info MrB. Apologies: negative outlook for Wintaai Holdings. In the US for the last 5 years, WC insurance has been an unusually bright spot in commercial lines. What's in store and what does it mean for Stonetrust? 1-In the last 5 years, Stonetrust has consistently underperformed on the underwriting side when comparing to related peers in the WC space. From AM Best and post above (2015-19), industry vs Stonetrust: 2015 95.8 109.6 2016 95.6 100.4 2017 92.5 99.6 2018 87.0 96.3 2019 88.3 89.6 avg 2015-9 91.8 99.1 2020 85-86 86.4 2-From available disclosure, it's not possible to assess the reserving profile of Stonetrust over time and it's possible (though unlikely) that higher combined ratios in 2015 to 2019 were related to more conservative reserves than average (accident year combined ratios closer to reality than peers) and 2020 may be the beginning of the realization of this aspect. However, it is estimated that net premiums written for WC declined by about 8% in 2020 (with rates not really moving) and, for Stonestrust, NPW declined by only 2.3% (retention stayed the same). Even if this may partly reflect that Stonetrust has been geographically expanding, more likely it means that Stonetrust may not be ideally positioned counter-cyclically for reserving. AM Best suggests that the WC industry has become significantly under-reserved. This is hard to confirm prospectively but AM Best has been pretty good overall with these reserve issues in the past even if exact timing is difficult to map. For example, their asbestos reserving deficit work has proven to be quite solid, over time. Just using basic historical assumptions, it's reasonable to suggest that the high amount of reserve releases of the last 2,3 or even 4 years (for the industry as a whole) will become a correspondingly large deficiency movement in the future. Stonetrust has written business lately with an above 100% accident year combined ratio (2019's CR was subject to a non-recurrent gain on the underwriting expense side). Reversing the positive reserve development pattern at this point while growing faster than peers is a recipe for further underwriting (calendar year) losses. 3-From the investment point of view, i suggest the hypothesis that results may be relatively positive in some periods but (IMHO) it's likely that net relative results will be inferior over the long term. A differentiated investment strategy is not well looked upon by regulators when results are poor. 4-A key concern is the message that WC (and Stonetrust) should do well with the market hardening. Since the WC seems to have a life of its own , it's unlikely to follow trends seen in other commercial lines. A positive aspect is the excess capital but what happens to this excess capital and the returns obtained may disappoint. ----- Additional comments about 2020 and the WC's insurance market and what it may mean going forward (for Stonetrust). In 2020, results turned out much better than expected with the direct and indirect Covid-19's impact. WC claims were less frequent (and especially less costly) than most predicted and most of the costs came from lost wages secondary to temporary quarantine measures. Results varied to some degree across states for a variety of reasons including general policy and specific coverage rules but positive trends were noted across geographies. An aspect which occurred which is amazingly unprecedented is that claims came down (during the downturn) both absolutely and relatively. In a typical downturn, claim frequency tends to go down absolutely but not relatively (this is an interesting phenomenon but likely not interesting enough to discuss here). This wasn't the case in 2020 and people are puzzled. Puzzled in the same way when trying to explain the conundrum now where employers are looking for workers and there is a significant pool of potentially available workers and, still, employers have difficulty finding candidates...This is likely closely tied to the centralized mandate (which has gone up one notch in 2020) which implies to centrally and simultaneously provide both work and help to the masses. This is bound to fire back if the idea is to encourage productivity in this mature (aging) economy/population and is likely to be a negative for WC insurance long term (payrolls) but transfers backed by the printing press will help WC combined ratios for a while still. ----- Stonetrust reports lower average medical claims per case and this may suggest (?) that this is related to better 'management' but, just eye-balling, it appears that the difference may be simply related to the states where they do (and don't do) business. Of course, everything above could be wrong. This should be an interesting re-assessment in 5 to 10 years.

-

From @gfp in the BHE thread (March 3rd 2021): "Berkshire basically facilitated the transfer of Sokol's stock to Abel by financing Abel's purchase of stock. That's how Abel was able to afford a block of stock currently worth over $500 million. Abel's BHE shares are convertible into BRK.B shares and that is what I ultimately expect to happen once Greg is CEO of Berkshire." From the recent BHE 10-K and proxy and further documented buyback of Mr. Walter Scott's minority stake, the fair value (the 1% of implied equity value) of Mr. Abel's stake is well above 500M at this point.

-

^My pleasure. i saw that you posted about the Robinhood platform and retail investing today and it's interesting to note that for Lloyd's, even if that aspect was neither necessary nor sufficient, the relative democratization of access for Names to supply capital into the Syndicates in the 70s and 80s played a role in the eventual outcome. When things turned out the way they did, the Names were not happy and complex court cases were initiated based on the concept that they had not been sufficiently informed...At least modern-day crowd investors don't have unlimited liability although there seems to be a belief that there is an unlimited ability to print money.

-

Ultimate Risk is interesting and the author does a good (and balanced) job at describing the events that led to the crisis. But like in the paper you refer to, the main reason for trouble at Lloyd's was growing capacity in a soft market (of course the softness is not appreciated in real time) in the absence of governance safeguards. You will like the book if you have an unusual interest in insurance (history etc) and Lloyd's evolution over time. The author does discuss the key players but basically it's a story about greed being stronger than controls, in a cyclical fashion. The book helps to understand why certain decisions were made (and not made) and looks into the 'psychology' behind those decisions. You may like the following also, which has some specific case studies: Actuarial Review of Insurer Insolvencies and Future Preventions Phase 1 – A Review of Root Causes of Insolvencies (soa.org) If you read what regulators have been writing about this topic lately, you will find that the idea that cycles have been conquered (with better understanding, risk grading etc etc) has permeated through the markets, an idea which, by itself is not worth very much and may be, in fact, a contrarian indicator. Going back to Conseco, the manufacturing housing financing crisis of the late 90s shared several common elements with the real estate bu**le that formed in the next decade across the board. Many who have dissected what went wrong at Lloyd's tend to focus on asbestos and pollution developing issues (as "black swan" events) but often forget the root cause(s) that build up over many years.

-

i just finished Ultimate Risk. Thank you for the recommendation. @LongHaul, AFAIK, there is no book about the following story but it seems relevant to your quest: Conseco, a life insurer with an unusually growth-oriented strategy and an unusually ego-centered CEO ended up buying a manufactured housing financing entity in the late 1990s. Mr. Buffett got involved in the bankruptcy proceedings after. As usual, red flags were defined afterwards (by most).