Cigarbutt

Member-

Posts

3,373 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Everything posted by Cigarbutt

-

Not as much a 'lesson' as a teaching moment for me. It felt as though a more material way to protect from reserve risk with covers and transfers was indicated during the 2017-9 period when it was felt that there were significant reserve deficiencies building in many lines, including casualty catastrophe (those developing trends can be a bummer; asbestos etc). But across the industry and, similarly (and relatively better) for FFH, these reserve deficiencies have not occurred, at least so far, and even if were to occur at this point, the solidly priced recent hard market period would likely buffer such trends. One needs to have an open mind and i was wrong about that (we had exchanged about this topic some time back). The following (offering of reserve risk mitigating products) explained that perspective: affiliates_maf_0319_3_lpts_and_adcs_for_risk_mgmt_dustin_loeffler.pdf (casact.org) Having said that, FFH was careful with rising premiums during that specific period by keeping a relatively low level of retention, which, in retrospect, appears to have been the right strategy in that part of the underwriting cycle. ----- Along the same conceptual line, FFH has decided to deal with interest risk in its own specific way and they may be right once again?

-

Yes, that's the fast and easy way to do it and likely works fine in most circumstances. With share-based compensation, there are potentially many valuation issues including timing issues. When shares move from the company to the employee, to calculate the compensation cost, one has to wonder if shares had been bought back before, are being bought back concurrently or will be bought back later. At least, when cash settled, you know that shares are being bought back concurrently and the tax-withholding-part of the share-based compensation is basically a cash bonus paid upon vesting.

-

Opinion: these look like operating decisions which are not material in the grand scheme of things. It's an exchange of reserves for premiums with a time value component and the buyers of reserves think that they can make a larger profit than the sellers, in this case Fairfax. It's likely tied to older business lines in run-off or semi run-off; FFH likely sells a small profit opportunity but gets a cap on adverse development on already incurred claims. These transactions can have small effects on statutory capital but that doesn't look like a primary reason in these specific cases. These are similar (in substance) to adverse development covers that FFH was fond of (example: the Swiss Re cover (remember those days?)) before finite reinsurance issues surfaced in the early 2000s.

-

When there's net settlement, the company withholds a number of shares that were dedicated to a specific employee in order to pay tax authorities (according to regulated percentages) in the name of that employee but it's effectively the same as if the company would have bought back these granted shares from the employee at fair value and then the employee used the cash proceeds from the sale in order to pay same taxes. Since it's share buyback activity in substance, it's still classified as a cash outflow from financing activity. Since 2016 (new GAAP standard), a lot of the stock-based compensation-related cashflows have moved from the financing to the operating section but not that specific one.

-

FWIW, i think this is interesting. Going from bottom-to-top, the wealth effect (at least the marked-to-market usual meaning, on consumption) is for real and happens at the margin although the effect appears to be quite limited overall. For example, this has been looked at in Japan (late 80s) and most evidence since then points to the same story. The Japan example below has a section on the effect of 'wealth' on consumer expenditures (and fixed investment for the Japan example). The Japan example is unfair because it's an ex post example of reversion to the mean (and more) and maybe this time is different.. VI Movements in Asset Prices Since the Mid-1980s in: Saving Behavior and the Asset Price "Bubble" in Japan (imf.org) Below is a personalized (and simplified + adjusted for an intersection point in Q1 2000) Fred graph showing the relative trends of income, household net worth and expenditures: The income is the main driver. Adding the personal consumption expenditures on durable goods (not shown here) results in a noisy graph but shows some wealth effect, especially recently and this may explain some of the momentum behind the likes of Peloton, Restoration Hardware and even Tesla? or even iPhone sales?? ----- Chart 6-7 in the late 80s article has a graph showing the relation between household net worth and income and it's sobering (who can say what really lies ahead?) to read that the authors (article published in the early 90s) 'felt' that stocks and the economy in Japan were back to their long term trend line.. Here's the recent US picture: The first added circle was when i started investing and the second circle was when i decided to plan for retirement. What's coming next?

-

@John Hjorth But where have you been? {Why do i get the feeling that some of those who are not heard may be the ones to listen to?} {Related to this thread, three of my off-springs are reaching autonomous adulthood and have started to ask questions, both backward and forward looking, about their investment portfolios, questions which they are not naturally endowed to integrate (capacity and temperament) and some questions which I was not ready for despite a tendency to try to plan for any scenario; perhaps I need to throw some questions out in the open? Or get outside and independent counsel?} ----- FWIW, in this environment, it seems that combining fortunes with family members may require some kind of long-term commitment (10-20 years?) and a no-questions-asked and sealed-trust component? What does long-term mean anyways?

-

Investments Benefitting from Higher Interest Rates

Cigarbutt replied to maplevalue's topic in General Discussion

Yes, in the last 20 years or so at least and apart from very muted episodes, we have lived in a world awash with excess and abundant capital. This has driven yields (forward) down across the board and this has been visible, for example, in the related alternative capital arena tied to reinsurance: insurance-linked securities. Shown below is the spread trend for catastrophe bonds: Higher spreads of earlier years were tied to learning how to price the products using a wider than usual spread and the returns were quite strong. Returns have come down and have pretty much paralleled junk bonds' returns since after the GFC years. Spreads have come down as a result of very abundant capital looking for yield and only moved up some with the very catastrophe-prone 2017-8 years. But abundant capital has come back with a vengeance. Interestingly, going forward and despite low spreads now and very easy money (still), the asset class is likely to outperform most other asset classes including high yield bonds which have credit spread risk (junk bonds have been trading at negative real yields and very thin spreads lately..). Hoping for a virtuous cycle again, somehow. Good luck with those "London" insurers. ----- Fairfax deserves another look. Running off legacy lines is pretty much history of the past and they have, consistently and for a while, reported positive reserves development in all material operating subsidiaries. The underwriting component for ROE looks good especially if they don't become hurt on the asset side (if ever capacity really becomes an issue again). If you think inflation is on the way and don't mind their relatively high equity exposure (with a 'value' skew), their fixed income portfolio is potentially positioned to take advantage of opportunities. -

Investments Benefitting from Higher Interest Rates

Cigarbutt replied to maplevalue's topic in General Discussion

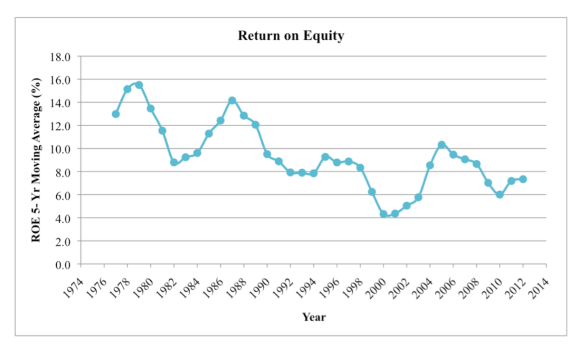

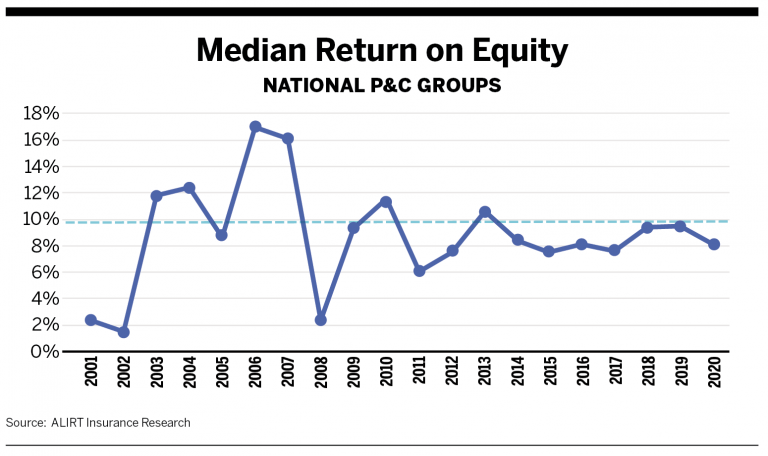

Interesting. In the Inflation Swindles the Investor, Mr. Buffett had offered the assumption that the corporate 'coupon' was sticky with ROE (OK volatile from year to year) pretty much stuck at 12%. It turned out this did not apply to P&C insurers after: ROE over time: ROE recent: With rates going down, nominal investment returns have tended to go down and combined ratios have also tended to go down. If one expects inflation/interest rates to go up, over time, there would likely be at least some inflation protection (through higher nominal investment returns). This is interesting now because there has been hardening in rates and likely some built-in underwriting profitability for a while. It looks like FFH is expecting this outcome. BRK would also benefit but more in the sense that it could benefit from more than one (almost any) scenario. It's interesting to note that with the 10-yr going down, insurers have been relatively slow (as a group) to strive for more underwriting profitability (insurers at large have been lamenting about this for a while but it's been partly due to the fact that it's easier to signal virtue than..). This aspect and settling for slightly lower ROEs explain the divergence. The wildcard is that nobody seems to be truly able to explain the long secular downtrend in interest rates and we are entering a phase when tightening is announced as real rates are at a record negative level. -

Too much of a good thing may not be a good thing. Evolution deserves a lot of respect because, through very high numbers of trials and especially errors over long periods, nature tends to identify the optimized processes for our bodies and behaviors. In the last two hundred years or so, humans have found ways to effectively compete with evolution but one has to accept that human efforts will be fruitless in the vast majority of these contests and that's one of the reasons venture capital makes sense. But most mutations spectacularly fail. How to make room for alternative theories? For example, when humans tried to reproduce delicate movements related to upper extremity dexterity, it was (eventually) discovered that the human template remained, more or less, the gold standard scheme. A similar story is happening with neural networks. Humility required here. The law of diminishing virulence doesn't always apply and black swans are possible. The above was suggested a while back (virulence vs contagiousness) and i added an area for omicron. The delta's relatively high virulence did not exactly 'fit' the supposedly down-sloping curve. Omicron was also a surprise (huge jump in transmission potential). Still, on a weighted basis of scenarios (what happens in general, with previous coronaviruses etc), it's likely that covid and related variants to come (genetic drift and shift) will become immaterial although endemic and regional outbreaks are likely to occur in a somewhat seasonal pattern. One major unknown is that the virus sometimes 'jumps' and there's still some uncertainty about the original 'jump' and six-sigma deviations are always possible but this is mostly the unknowable-unknown territory so.. One thing which is not much talked about is that a very large and populated area (China) has chosen a very rigid containment strategy (so far) and herd immunity is only partial (natural very-very-partial and vaccine-partial). It seems like this strategy is not sustainable with omicron and related which transmits so easily and it's hard to envisage a scenario (given their tendency to use a binary and centralized approach) where the tight approach does not show major cracks in the foreseeable future. Viruses are not known for their patience or intelligence but they have evolution on their side.

-

The title of this thread is a Top is Coming but it could be a Bottom has been Reached (rates). Rates (including mortgage rates; isn't it bizarre that the tax payer is almost guaranteed to participate over the duration of the fixed social contract?) will eventually go up, perhaps big time but when? In the 1970s when inflation became embedded in expectations, it felt like a self-fulfilling prophecy, but, despite real noise, wage inflation was ahead of consumer inflation: And for the last 12 to 18 months, it's the opposite trend: In today's inflation, there seems to be an unusually high number of people (mainly at the bottom) who wonder who took the cheese. Some say necessity is the mother of creative destruction.

-

Investments Benefitting from Higher Interest Rates

Cigarbutt replied to maplevalue's topic in General Discussion

i clearly don't have an answer to your question but insurers have a fair amount of flexibility in dealing with interest rate risk exposure (it's mostly more qualitative than quantitative so..). There is a tension between the companies (outside of the institutional imperative) who aim for higher ROEs as a trade-off to higher solvency risk and regulators aim for the opposite so.. For a real-life example of potential outlier characteristic, here's a piece of FFH's annual report in 1999 when they were still fascinated by the Japanese 'experience': Left unsaid was the associated difficulty in dealing with negative cashflows at insurance subsidiaries operating in a declining premium level environment but it goes to show that interest rate risk is a two-edged convex knife. FFH though has changed in more ways than one and now (AR 2020): "At the end of 2020, our fixed income portfolio, which effectively comprised 73% of our investment portfolio, had a very short duration of approximately 1.8 years and on average is rated AA. As we said last year, we do not expect rising rates to materially impact our fixed income portfolio." Opinion: this appears to be a most difficult period for the fixed income management of float portfolios and the odds of recognizing a loss for buy and hold strategy related to safe long term bonds have never appeared so much "guaranteed" but sometimes it get darkest before the dawn. In the land of the apparently ever rising sun, they are still expecting rates to rise and don't even hold the title of hegemonic reserve currency. -

Thank you for the answer. The cross-country comparison adjustment makes sense. i'm still looking for the best answer for the public-private question in the US and it seems that the public-private ratio has gone up some in the last 20 years which is interesting if the GDP-public-market thing is not completely flawed. ----- Added for perspective: Is the last spike a factor behind the notion that 50-70 % of people are living paycheck-to-paycheck? Disclosure: rhetorical question; no need to answer.

-

Investments Benefitting from Higher Interest Rates

Cigarbutt replied to maplevalue's topic in General Discussion

^i think gfp's comment was tongue-in-cheek and referred to BRK (longer-term bonds to assets = 1.97% as of Q3 2021) with the rest of float coverage in cash and very-close-to-cash Treasury Bills. One could reasonably criticize the aversion to reach for yield in the fixed income space (most insurers have been slowly drifting this way to various degrees with slowly and gradually higher exposure to lower graded bonds, CLOs etc (including RE last time i looked)) but Mr. Buffett had made this inflation "fear" very clear in his communications to owners since the 1980s. Example from 1987: "Both the timing and the sweep of those consequences {inflation and even possibly runaway inflation} are unpredictable. But our inability to quantify or time the risk does not mean we should ignore it. While recognizing the possibility that we may be wrong and that present interest rates may adequately compensate for the inflationary risk, we retain a general fear of long-term bonds. (my bold) "A company like that would surely be more valuable if rates rise." Mr. Buffett however has also said not to expect cash at BRK to rise to 150B (149.2 at end of Q3) so who knows about sweep and, especially, timing? -

There are many reasons why this measure may be flawed. Do you refer to any hard evidence versus the trend in share of corporate public or private ownership in the US, in the last 20 years or so?

-

Hi @LongHaul, i could defer to Spekulatius' "expert"ise, this site should really focus on investments and believe that potential for online rational discussions is entering maximum bear market but still extremely bullish about the future of constructive engagement. The rise and fall of rationality in language | PNAS Anyways, nasal irrigation is not up my alley and ENT colleagues seem to have mixed 'feelings'. The study is interesting but the design has the potential to introduce huge selection bias (and unreliable outcomes). The people who are included and agree for the 'treatment' may have an unusual set of attributes. Opinion: before large scale use, the work needs to be replicated using a more standard protocol. Apart from some costs and time value, there is very little downside although it's been reported that nasty deep-seated infections can occur when tap water is used (incidence similar to Guillain-Barré paralysis after covid vaccines; extremely rare but real). Anecdotal #1: recently (true story), i had some exchanges (on another board, covid subsection) with a participant who supported (with some evidence and using a similar conceptual approach although on a more distant mucosal surface) colonic irrigation as a preventative and therapeutic measure for covid. The opinion i provided came along the same line as the above except that i would not support both lavage techniques simultaneously using a close circuit. Anecdotal #2: thank you for this idea since during the review leading to this post i asked my youngest daughter for help (she's turning 15 in a few days) and we really connected when she showed me youtube videos and TikTok segments showing real people doing the real thing. Humans are fascinating. ----- Alternative hypotheses are critical but there has to be a way to effectively separate the wheat from the chaff? Numbers are starting to roll out and, in 2020, US health expenditures increased by 9.7% (up by 1.9% ex-covid) and reached 19.7% of GDP. Rinse and repeat?

-

^Anecdotes are interesting and it's entertaining to see how individual 'right' to choose may, at times, override the right choice, especially on a tribal level. Before anecdotes and if into post-mortems, look here: Disclosure: potential bias for choice of countries; used only as an illustration and using covid-death rates as a proxy for covid disease burden ----- Many variables involved (fundamental and sentimental) but vaccines (and vaccine hesitancy) eventually became major differentiating factors (less so going forward assuming an expected transition to lower grade and variable endemicity). Here's a reasonable 'model' (one can argue about extent of effect but they're in the right ball park; pre-omicron) revealing the previous benefits of vaccines: The U.S. COVID-19 Vaccination Program at One Year: How Many Deaths and Hospitalizations Were Averted? | Commonwealth Fund ----- On an anecdotal level, covid (especially with impressive omicron spread) reached a majority of people in my extended circle but my inner core has remained, so far, covid-free despite significant real-world involvement. Our in-laws, with whom we visit daily (basic care with a limited number of fair quality life years left) to help with residual autonomy, will likely catch it at some point but the disease burden risk has become quite manageable, especially at this point. On an anecdotal level, i've spent a considerable time 'fighting' stupidity on the internet (not here anymore) and it has felt, at times, like Don Quichotte. Also, i've volunteered for vaccination efforts (99% of people who come now have already been vaccinated; the vaccine fear hysteria is relatively low around here but has been growing also). Personal note to American friends. i live in a socialized medicine world and, historically and when still involved in hospital care, January was always a difficult period for hospitals (elective care postponed etc) because of the flu disease burden (Canadian hospitals have basically inexistent excess capacity) and it's mind-boggling (opinion) to see so many US hospitals being over-burdened by such a benign virus as omicron. i'm afraid you have become socialized and have not realized it ("Don't touch 'my' Medicare"). Final note: i visited Belgium in 1996 (and liked it). i remember well because we were driving around a lot and my wife often had bouts of nausea which eventually prompted a pregnancy test. The rest, as they say, is history.

-

Yes macro stuff is almost always a waste of time unless one finds the topic interesting. An aspect that often comes up in 'discussions' is that people use a multi-variable equation (which has a sound basis) and then hold everything constant except their own 'proprietary' explanation. Speaking of a potential limitation in one of your conclusions is that there seems to be an assumption that investments and savings remain constant over time which, obviously, does not apply. Maybe it's old school but future profitability tends to be correlated to previous productive investments (funded by capital and/or debt). For example, in the US, during the period leading up to the late 1800s, there was a significant trade deficit (mostly from finished products) but this deficit was used to build future productive earning power. The US even became a surplus nation for quite a while after. Maybe these things come in cycles too. Note: did you really mean "smaller trade deficits"?

-

Can i provide additional perspective? (a QE i remember discussing this aspect here (a QE thread, around 2018) with a poster who had suggested that it was expected that the green line would compensate for the red line after the GFC. At the time, i was wondering if there was excessive compensation and now.. Anyways, if the theory applies that the green line moving from 55% to 40% around the dot-com period "caused" a recession, i wonder what it would take this time. When i trained, this concept was called habituation and in the macro debt world, i've learned that some people call this marginal revenue product of debt. Some even say that sometimes one tends to get less and less bang for the buck.

-

In the spirit of the Christmas period, a wish to all for health and happiness. In the spirit of the essence of this site, a wish to all for peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice. 2022 is shaping up to be an amazing year.

-

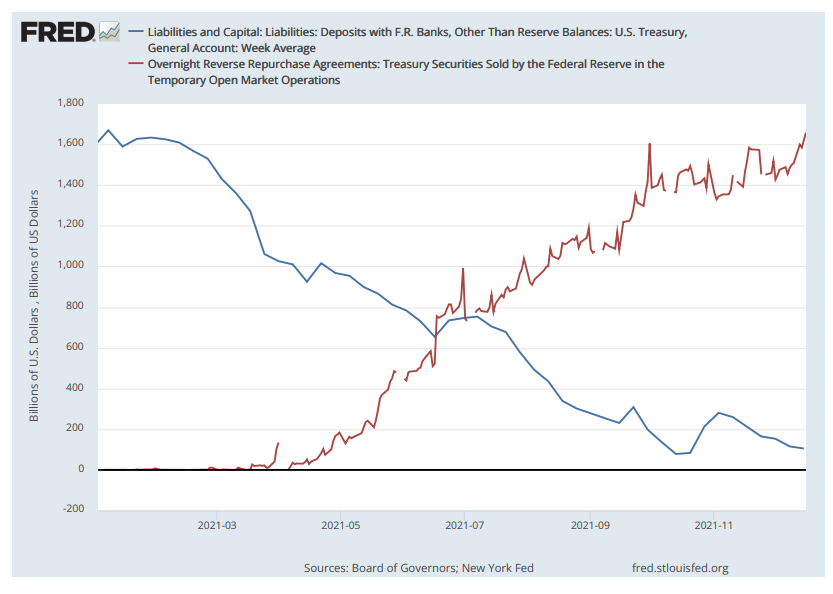

Hi wabuffo, The idea is not to turn this topic into an ego thing and it's not clear if there's any use for 'real' investments but the money stuff, like it happens at times, has become quite interesting. i guess the dilemma is related to how much weight one wants to allocate to 'reserves management' vs Treasury 'working capital management' for the TGA. Here's a tampered with graph, eliminating the noise (IMO) from movements in the TGA account since the negative trade balance issue related to microbial disease: Such huge movements in reserves were simply unimaginable just a few years ago and it's expected that technical issues happen during implementation. When the US Treasury issued Liberty Bonds in 1917-9, the amounts issued were unprecedented and there were timing issues (amounts raised in advance for future expenditures). There were significant concerns with liquidity issues in the system and the Treasury (Fed was an infant then) didn't want to drain all this cash and to have the cash wait "on the sidelines", sort of. The TGA didn't exist then but they figured out a technical way with commercial banks to attenuate the scarcity of cash effect by using commercial bank accounts that would temporarily create money and smooth the accrual issue. Of course, then, the key were not the technical issues but the ability to change the name of the Liberty Bonds, that became the Victory Bonds. Winners write the history books. Anyways, i think (FWIW) that, in early 2020, there was still huge room for excess reserves build-up in the system (in Japan excess reserves are now more than 100% GDP) but the Fed's decision to not renew the SLR rule relaxation for commercial banks as of March 31st 2021, resulted in a pretty much dollar for dollar movement from the TGA to the overnight reverse repo facility. From this perspective, it would have been possible to simply allow banks to pile up more risk-free securities on their balance sheets. The ON reverse repo facility was 'created' in 2013 and was supposed to be temporary. There is nothing more permanent than a Fed temporary tool. ----- And yes the above may be flawed. Today, i tested the outside Christmas light setup and looked like: Happy holidays!

-

^From end Q1 2020 to now: -The Fed 'absorbed' 45% of all Treasury paper issued -90% of Fed printed money was used to buy/swap Treasury notes and bonds (minimal amount for bills) -Over the period, the Fed 'absorbed' 83-85% of all Treasury notes and bonds issued About control (yield curve kind), i wonder.. "Circumstances rule men; men do not rule circumstances." Herodotus

-

I was just wondering how money transferred from Spekulatius’ wife account to (with some basic accrual short term adjustments during the transfer) another private account (for example, someone in the community who just had her account credited with unemployment benefits) results in an enduring change in 'excess' money supply.

-

If understood correctly, I-bonds outstanding were at about 180M in mid 2021. Can you walk me through how buying a savings bond results in a reduction of excess money supply?

-

This thread and specific post are interesting. In a relevant way for 'diagnostic analytics', there was a publication showing superiority of the model output over human output for a specific task: from a picture, decide if the skin lesion was benign or malignant. After peer-review (humans still in the loop), it was discovered that the computer 'cheated' as it associated the presence of a ruler in the picture with a higher risk for malignancy and this was simply indicating a certain level of the concern by the human who tended to measure (with a ruler) the lesion when the human somehow 'felt' that the lesion had malignant characteristics. So, once this 'bias' was removed, the superiority of the model decreased significantly. A fascinating aspect is that the multi-level algorithms will tend to integrate implicit human biases when mixed within the supposedly 'raw' data. This area is still in infancy but the potential is huge. It's likely that the best outcome will be a variable hybrid 'system'. The origin of AI's output can be well traced but poorly explained (black-box 'reasoning') whereas the origin of human brain's output can be well explained (not always..) but poorly traced. This aspect is also relevant for investing i guess. Personal and anecdotal comment: since graduation, there's been this huge (and welcome) movement to improve the human side of the (diagnostic and treatment) conversation and now 'machines' are about to take over the world..

-

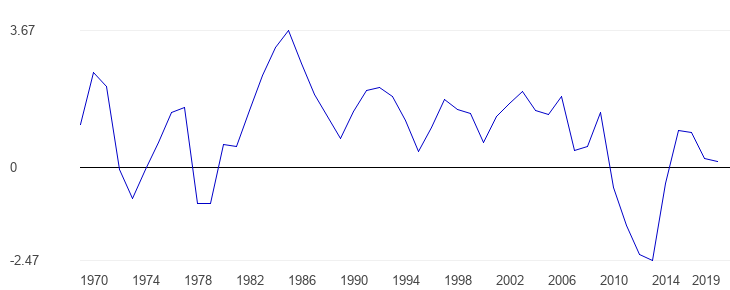

^Potentially relevant perspective? Using the MV=PY perspective. It's only a balancing equation; don't get angry at it. Since their bubble burst (1990) and up to recently (covid new era?), this balancing equation has revealed one of the most constant (and remarkable) relationship in financial history. Long story short, the PY (nominal GDP in Yen) is essentially the same as 30 years ago(!), ie barely above and close to 0% CAGR. V (let's call it a simple mathematical residual to avoid the 'velocity' controversy) has gone down almost linearly by about 2-2.5% per year. To complete the balance, the money supply growth (using M2 as proxy) has gone up by a rate of about 2-2.5% (with the government increasing base (outside) money to compensate for private deleveraging that has happened over the last 30 years(!), a true bu**le, that was). Corporate loans being repaid over time, on a net basis, will cause money to be retired (i guess 'destroyed' would be a better term to reverse 'created') from the total money supply. A fascinating aspect is that Japan, over time, has increased the relative proportion of base money to total money supply as a result of long-lasting QEs at the expense of inside money. Note: this ratio has increased in the US since March 2020 but is still way below Japan. If crowding out is a thing, this is something to consider if long term productive growth is the goal. Now the interesting part is what has been happening recently as the linear relationship seems to have entered non-linear territory with money supply growth growing by 8-10%, growth remaining stuck in the dust and inflation staying at zero. ----- Random thoughts: -The population in Japan is about the same as in 1990 but the population aged 15 to 64 has decreased significantly (by about 10 to 15%). Older folks in Japan (contrary to other developed countries) are walking faster and have more teeth but Japan is at the forefront of something humans have never experienced before (but others are catching up real fast, including the 'developing' China). -The private sector in Japan 'only' holds 90% of JGBs that the BOJ does not hold (about 50% of total) but, given the huge amounts of JGBs per unit of GDP, it's still a large absolute amount (people are entering a dissaving phase there, at least that's what is expected of people reaching their end, especially if they live longer, various variants permitting). -Japan's trade surplus is often taken for granted but trends show that trade deficits could rapidly be in sight if the exchange rate continues to be associated with recurrent waves of sympathy for the Yen as a safe haven. Of note is that Japan global trade as % of GDP has gone from 20 to 35% since 1990, which implies that unfavorable trade terms would have quite a significant effect on capital movements. Shown below is the % of trade balance per GDP for Japan over time including their 1980s China moment.