scorpioncapital

Member-

Posts

2,857 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

2

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Everything posted by scorpioncapital

-

Well let's look at it like this. I've seen stocks with puts that are 30-40% OTM. The yield on collateral retained by the brokerage is 20% for 6-8 months. Furthermore the company is buying back stock in significant amounts. Fed put AND company put floor under the stock price. Care to calculate the odds of an adverse event vs a favorable one?

-

Compilation of all Leucadia shareholder letters

scorpioncapital replied to Liberty's topic in General Discussion

What I find striking is their evolution. The first 5-10 years you couldn't tell what was happening. It looked like a pretty cut and dry financial company. It really hit home the message that you have to really know the management in these situations and what it is they are doing. It didn't seem at all clear, only later did the letters become more "folksy" like Buffett's letters. -

Compilation of all Leucadia shareholder letters

scorpioncapital replied to Liberty's topic in General Discussion

It's interesting as a historic document, but I don't feel that Leucadia today has any resemblance to these events. It's under new management and looks quite different. -

Psychology of buying a stock at a certain price

scorpioncapital replied to frugalchief's topic in General Discussion

"The reason lies in the fact that you don't know @ the time whether a better opportunity will show up in the near future for you to deploy the cash. So buying @ 1.3x BV could be an issue if better opportunities arrive." Couldn't you just issue stock and/or sell stock in the acquisition even if you bought back your shares? That way you can hedge no opportunity with the flexibility to buy something big if it came along. -

I was profoundly intrigued by horse betting recently in Vegas and a simple strategy of betting only on highest implied odds in the expectations market with no consideration of fundamentals. I was surprised how well this worked. It seems a crowd often assesses odds quite accurately and was thinking if anyone knows how this might work with stocks. Is there a quick way to determine the implied return expectations of a given stock price? Eg.. Given any stock price, what are investors in aggregate implying as their return goal?

-

How long do you wait to achieve expected return?

scorpioncapital replied to scorpioncapital's topic in General Discussion

My eyes are popping out at all these references to 20,30,40,50% returns. Am I the only one not getting these? -

How long do you wait to achieve expected return?

scorpioncapital replied to scorpioncapital's topic in General Discussion

"If my thesis is not based on growing IV but a sum of the parts or a future event then you are in danger of having missed something important in terms of timing or cost. " Unless it's losing money, every company should be increasing IV by some amount. Although sometimes the IV is a drip. Then there is the issue of cyclical businesses. Low points in a cycle could add maybe 5% per year to IV but it has to be averaged out with the good times. It seems a business cycle would be a good proxy for holding period. Not sure if there are any studies showing the ebb and flow of American business cycles over the years to see how long they generally last. -

How long do you wait to achieve expected return?

scorpioncapital replied to scorpioncapital's topic in General Discussion

With Ben Graham investing you almost have to sell out after 3-5 years if your return expectation is buying a 50 cent dollar and getting 20% and it doesn't happen. So actually the next question becomes if your return expectation isn't met, do you bail or do you set a new period of lower expectations? Suppose you wanted to get 20% and after 5 years you end up getting 0%. Do you now say, ok, I'm willing to settle for 13% and give it another 5 years or maybe even still have the same goal but extend the yardstick or just start from scratch again and try to find a new security that you know as well as the one you own? -

How long do you wait to achieve expected return?

scorpioncapital replied to scorpioncapital's topic in General Discussion

Interesting discussion. I wonder though how much of these timeframes are the product of recent experience? 3-5 years seems rather short. There were times in the 50s,60s,70s where one had to wait much longer. The other issue is what happens if you are wrong on the undervaluation? If this happens one may get out just when the stock actually gets cheap. Well, really this question is kind of like marriage if you are a long term investor :) -

Average Stock Market Returns Aren't Average

scorpioncapital replied to Ham Hockers's topic in General Discussion

What I found interesting was the link between volatility of return and final return. He seems to argue that a volatile return of the same magnitude is less preferable than a stable one over time (obviously) and slightly lower (maybe less obvious). So we've heard value investors like Buffet say that they prefer a lumpy 20% vs a smooth 15% anytime. In this case, what they are saying is that a lumpy higher return is still higher than a gradual lower return. But perhaps implicit in this is that the lumpy return be high enough to compensate for that volatility, otherwise, any reasonable investor would just take the gradual return. -

Question for Canadian users of Interactive Brokers

scorpioncapital replied to Liberty's topic in General Discussion

I've had 30% margin maintenance and initial on S&P500 stocks with IB Canada since at least 2008. -

Question for Canadian users of Interactive Brokers

scorpioncapital replied to Liberty's topic in General Discussion

IB offers 30% margin requirement on S&P 500 component stocks. I always thought this was standard across all brokers but possibly not. As for margin calls, they are "pretty nice". They'll let it go minus 1 to 2% of total stock value (appx) up to about an hour before closing before acting automatically. -

invisible bankers was pretty good, I just read it yesterday. I really liked the chart that showed how many dollars customers actually get paid out for different types of insurance. Title insurance was really the most profitable, it isn't really insurance, just legal research. It was interesting to see that speciality insurance is the best gig in town for companies!

-

I've been looking at several DEF 14s and it has made for some fascinating reading. Specifically, I've been looking at what boards set as their targets for performance-linked compensation such as special bonuses, options, and RSUs. For example, one thing can be seen is that for companies where return on equity or growth in bv/share is the primary performance target, compensation varies wildly for the same or sub-par performance. Some have targets set at 11% return on bv, others have 15%, some have payouts that are significant even below target. Some businesses are simple, others complex. I'm thinking why not choose the least amount of compensation for the highest target? Does anyone know if the annual targets are a moving target or are fixed? Clearly if you move the target each year based on a compensation advisory board or firm, you're changing the benchmark and it seems unfair. Other DEF 14s actually have no targets and they say, we compensate at our discretion. Some of these boards have compensated far more than those that had a target and some far less. In short, do companies believe their industry dictates compensation, or their own personal circumstances? Some for example, will compensate for a large acquisition, even though that is subjective whether it creates value.

-

Which type of insurance has the best economics?

scorpioncapital replied to scorpioncapital's topic in General Discussion

I've experienced this strangely enough in Google advertising. You can go for multi phrase keywords or strange combinations with high click through rate but like 5 clicks a month. You may even pay nothing for it and get a high return. Or you can go for a big generic keyword and get huge volume, expensive cost and try to make it up on your skill. It may even be huge volume and low cost and still be profitable. In the end, it always seems to come down to finding a niche. In this sense, I have to agree with the idea that some sort of specialty insurance is best. What about re-insurance? Are the dynamics of that any different? -

Which type of insurance has the best economics?

scorpioncapital posted a topic in General Discussion

From a purely theoretical standpoint, there are many types of insurance stocks and rates, is there one that has better economics? There are - Mortgage Insurance - monthly premiums, low risk of default, relatively predictable, very commodity like. - P&C - Reinsurance - Speciality Insurance - Auto insurance etc... -

"shorting" indirectly such as in options can reduce collateral requirements so if you think the stock will be in a range for a given amount of time, and you don't want to lock up your capital, this is a necessary component.

-

"Equity markets are overvalued" - James Montier

scorpioncapital replied to a topic in General Discussion

"Does anyone really think the S&P could drop 70%" If the money supply doubles, the S&P500 will have effectively crashed by 50%. After the initial margin calls, it should zoom up like crazy. It's the same argument that the US can never default in nominal terms on its debt cause it can always print money to pay the bonds. But it can very much default in real terms. So in the end, it is the shaking out due to volatility of over-leveraged players that becomes the primary danger -

I would think both servicing and private MI are both low margin businesses. In one, you generate a fraction of a percent on servicing the loan and in the other, you receive a fraction of a percent of the total mortgage as a premium. I believe companies like Ocwen are outsourcing their collections to India to reduce costs, how much can they make of the total mortgage for this function? MI appears like a business of writing deep out of the money options. You collect a pittance of a premium but you don't expect to be exercised (or rather you don't expect - in the aggregate - to pay out a large part of your premium as many events have to happen for a default to occur). So the constraints are a) how much business you can write and b) how much money you make in relation to your equity base. Just to see how razor thin it is , you are making like 0.5% in premium on the amount of the mortgage. Right now return on statutory capital are very fat - something like 38% if you include the unearned premium. But it would seem that reserves for losses and a buffer require an equity margin above and beyond minimums. Thus I see returns in the mid teens to 20%. The unearned premium appears to be some sort of float while the earned premium is pure profit if the reserves for losses are accurate and things go well.

-

buying stocks with margin vs buying stocks with float

scorpioncapital replied to muscleman's topic in Fairfax Financial

I also wouldn't say that "term loans" imply no discomfort. Have you noticed during the financial crisis as the price of equity fell, it was almost like a margin call? Some companies went bankrupt, others had to restructure their balance sheet. This was also seen when naked short sellers pushed the price of the equities lower, even if it wasn't justified. -

Yes, I believe today you can write high FICO insurance and generate 20% return on statutory capital. What I've noticed is that the insurers trading at 2-3x book. So let's say leverage ratio is 16:1 (which appears to be the line in the sand for regulators on leverage limits to be compliant with Fannie and Freddie certification) and you have 500 million in statutory capital. You can write 8 billion and earn 20% = 1.6 billion. Add your paid in capital and let's say 2 billion = 4x book. Obviously this is "fair value" and there should be some discount and profit potential for the investor coming in. I would imagine if you paid 2x book in the above scenario, you'd have a potential to double your money. This is why it seems puzzling the multiples are so high, where is the profit potential for the incoming investor if he is "pre-buying" the future profits unless you assume higher leverage than 16:1 and/or higher than 20% returns. Also, you may assume some return on the premiums. For simplicity, I usually just assume that the discount rate for the earnings = the return on the investments. If this holds, you can cancel out and assume the above numbers directly.

-

Makes sense, thank you. Another puzzle for me is the valuation of the mortgage insurers. Most of them trade at 2 or 3x book value. This is a little "alien" to me for insurance operations. I am used to the idea of 1x book value as a starting point. Is it simply due to anticipation of a high growth rate or is there something about the value of the underwriting that makes it more valuable? With servicing, I can wrap my mind around the value of servicing rights and free cash flow yields while the servicing runs off.

-

buying stocks with margin vs buying stocks with float

scorpioncapital replied to muscleman's topic in Fairfax Financial

Every company in the world leverages through margin. Look on the line on the balance sheet that is labelled liabilities or corporate debt or bond issues. And every company pays a price for it. Insurance you have the chance, but not the guarantee that the rate may be negative (e.g. Berkshire which is an exceptionally run operation). Some insurance operations can even turn the liability into equity by releasing acquired reserves - this is almost like having part of your principle forgiven. Over time and large scales, the cost of funding of insurance may provide a distinct advantage - or it may not. There are also regulations on how float can be invested for most operations depending on type of premiums written, statutory capital , etc..If you look at most insurance companies 50% plus, if not 90% plus of float is fixed income. These companies will never be allowed to own anything else. Here it becomes a closer race between borrowing at say 8% and investing 100% in a business for 20% returns and an insurer borrowing at 0% or even -2% and investing 100% in bonds at 8%. 8% * 3x float = 24% roe - (cost of float) 8% debt * 1.5 leverage * return of investment purchased (e.g. 20%) = 30% - 8% = 22%. As you can see, it's a very close race. -

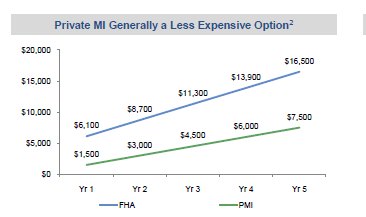

I see servicing as sort of a low margin collection business. I'm starting to conclude insurance is a "cleaner" way to play the space too and returns are good at the moment, generally seeing 20% returns on writing what in effect is a deep out of the money option (e.g. 20% payout on a 750+ FICO score customer where they put in 5%-15% down, if a default occurs and the bank can't sell the property except for a big loss). There's a lot of things that must go wrong for such a payout to occur. In the meantime, you collect these premiums and with rates going up the investment portfolio could generate respectable leveraged returns. PS... do you know why FHFA mortgage insurance rates are double to triple the price of private MI rates? I think this fact is the key to a real arbitrage and why this sector is poised for growth. The chart below is from an Ocwen presentation and based on a $200,000 typical mortgage. Clearly, private MI can't be underpricing so severely so I'm trying to understand what's happening.