nafregnum

Member-

Posts

273 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Everything posted by nafregnum

-

Great podcast episode recommendation thread

nafregnum replied to Liberty's topic in General Discussion

The perfect pairing to "Scam Inc" is a longtime favorite called "The Swindled Podcast" https://swindledpodcast.com/ The guy who does the podcast lives in TX somewhere, calling himself "A Concerned Citizen", and he does deep dives into the stories of greed motivated criminals -- some are about corporations (product safety coverups, pollution disasters, etc) and some are about individuals. There's insurance fraud such as faked accidents, faked deaths, faked car wrecks ... I think he was first to thoroughly research and release an episode about the man who rigged the McDonalds Monopoly prize jackpots. Listening to this podcast is a little bit like a class in defense against the dark arts. -

Great podcast episode recommendation thread

nafregnum replied to Liberty's topic in General Discussion

The Economist put out 8 episodes about a Crypto Investing scam called "Pig Butchering" and it's excellent. https://www.economist.com/audio/podcasts/scam-inc Looks like the first three episodes of this series are available without a subscription to The Economist. I listened and enjoyed the whole 8 episodes, but just hearing the first 3 would be time well spent, and the rest of the details about this new "Pig Butchering" scam are likely to be online in other formats if you're not interested in subscribing. -

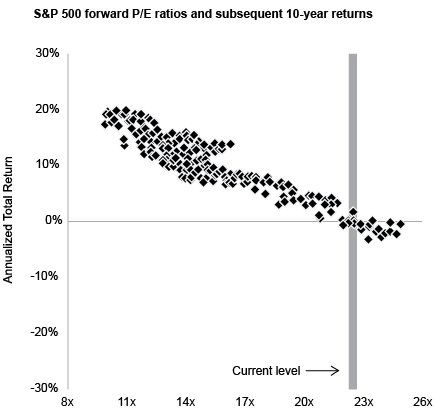

https://www.oaktreecapital.com/insights/memo/on-bubble-watch The recent memo from Howard Marks was in a browser tab, probably from when @james22 originally posted it here 12 days ago, and I finally read it today. I really appreciate how Marks takes the time to put his thoughts out there, and recommend checking it out. He's not calling a top, or saying that the market won't keep going up, or that the Mag 7 are in bubble territory, but did a fine job of describing the traits that past bubbles have shared. He included this chart that a couple people had sent to him: Here's the relevant explanation of the chart: I'm asking myself what to do with this info? I'm not heavily invested in the Mag 7, so if the top 7 falter, my guess is that a lot of that money would flee into other areas of the S&P 500, but I won't gain much from that, since my largest positions are not in the S&P. I'm only at 1% cash right now. Buffett's cash position is at a record level above $320 Billion, so it can't be the worst time for me to trim back and raise more cash. I'm only commenting about how I feel about my own portfolio and not giving advice.

-

Movies and TV shows (general recommendation thread)

nafregnum replied to Liberty's topic in General Discussion

Dostoevky's best English translators are a married couple, Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. They're fantastic, very much worth seeking out their versions over earlier translators: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Pevear_and_Larissa_Volokhonsky#Translations_credited_to_Pevear_and_Volokhonsky -

Christopher Bloomstran doubling down on DG and DLTR which are both at 5y lows. I'm waiting a little longer to see if those get even cheaper after Trump starts the tariffs. https://www.dataroma.com/m/holdings.php?m=SA

-

Thanks for this! Very interesting interview - I bought "The Prize" on Audible (it's abridged, so only 2.5 hrs) and am excited to listen to it. So, Oil was a main character in the 20th century world drama, alongside nuclear weaponry. Seems like we're looking at advanced computer chips as the current alpha resource, and maybe electrical energy like Yergin said around 55 minutes in when he said Bill Gates mentioned data centers used to be measured in CPUs "20,000 CPU data center" and now it's a "3 Megawatt data center" ...

-

Thanks for posting that video - I didn't know any of that about wastewater. I caught myself wondering what the dynamics are like up in Alberta's oilfields. I think the pressure of the injected water eases as the water is able to spread out into the geological formation until pressure is equalized. I imagine one cheapish solution might be to drill more re-injection wells and just pump slower into each one. Seems like that might reduce seismicity and also the risk of causing nearby zombie blowouts. Here's hoping they figure it out.

-

Starting a position in SNDL

-

I've enjoyed reading this thread today, mostly for all your thoughts on holding periods and concentration. Letting my winners run has usually been my best move. My big regrets have been failures to take larger positions when I feel like I've found a winner. Haven't bought anything this year, but sold off a little GLASF to sleep better. My main taxable account looks like this - I think I bought Booking, Citi, Nintendo, and Disney last year, but I didn't feel high conviction so didn't make them large positions. Looks like I sold off most of my losers to offset gains from selling some old winners last year, so the screenshot isn't a good picture of past failures such as BABA. I was lucky to follow a lot of you guys into Energy a few years back, particularly Obsidian which I had been in and out of earlier when it was PennWest -- big thanks for SharperDingaan for defending his rationale on OBE back when it was turning around and it was still unpopular. I should've listened to him about energy being something you don't hold for the long term. I wish I had sold above $10 when Russia invaded Ukraine and oil prices were surging. My best performer and my biggest position sizing regret was Enphase, bought back in 2017. It turned into a 200 bagger before I sold off most of it, and now I just keep a sliver as a memento. It was only a 0.1% position, DAMMIT! That old lesson from Enphase influenced me to build up a bigger position in GLASF a year or two ago. Buffett has said he's proud never to have lost more than 5% due to a single bad investment - I think he said Tesco was his largest mistake ... so, if I feel particularly convicted about something, I might take as high as a 6 or 7% initial position size. The way I think about it, If I were to hold a lot of 1% positions I'd probably be better off just buying the S&P. When I'm tempted to get more active, I remember this story I heard about research at Fidelity. (I asked Claude-AI to tell the story since I didn't want to type it out)

-

Watched this one last night, based on a reddit.com/r/Documentaries recommendation thread. A lot of real good philosophy on teaching/training in here that doesn't just apply to horses.

-

https://blog.gorozen.com/blog/is-us-oil-production-surging This article is suggesting shale production in the US is going to be peaking this year, that 50% has already been extracted from all major shale basins, and that the reason for recent growth has been prioritization of best performing areas, a process known in the mining industry as "high-grading", and that the actual figures are hidden behind some funny accounting using an "EIA Crude Adjustment Factor" (graph shown on the page) ... Opinions on the usefulness/accuracy of this information? Is this the kind of information people will be pointing to if Warren Buffett's big OXY bet plays out fantastically, or am I reading a conspiracy theory website?

-

Great podcast episode recommendation thread

nafregnum replied to Liberty's topic in General Discussion

Ooh, thanks, I didn't know anything about Pocket Cast before - I'm going to check it out. -

https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/methane-detection-just-got-a-lot-smarter/ Detecting methane leaks via a new satellite that the Environmental Defense Fund will be launching in a month or two, with support from Google and some funding from Bezos Earth Fund. https://www.bezosearthfund.org/ideas/satellites-for-climate-and-nature https://blog.google/outreach-initiatives/sustainability/how-satellites-algorithms-and-ai-can-help-map-and-trace-methane-sources/ It will have the ability to detect methane concentrations down to the resolution of 400m square pixels, and can watch 200 sites that are 200km square, so it'll be able to keep an eye on all the major O&G basins to identify where the worst leaks are so they can be remediated. The old quote comes to mind: "Only when the tide goes out do you learn who has been swimming naked." I have read that Obsidian Energy prides itself on its monitoring and leak prevention/remediation program. I'm interested to see what this kind of transparency does. I've heard that North American O&G extraction is much cleaner than in other countries, but we will all soon find out.

-

Great podcast episode recommendation thread

nafregnum replied to Liberty's topic in General Discussion

Overcast. It has "Smart Speed" (cuts out silences) and you can also pay $9.99/yr for some premium features, like ability to upload your own mp3 files to your own private 10gb of file space. I take epub books that aren't available on Audible, and convert them to mp3 file using some scripts I wrote and Amazon's Polly service, then upload the mp3s so I can listen to them. The app is great, even if you don't need to premium features. -

https://pracap.com/just-smash-the-buybacks/ Kuppy's rationale seems well reasoned for profitable-but-unpopular companies like O&G and coal. Obsidian (OBE) is doing buybacks. Who else is in this unpopular sector and doing buybacks at cheap valuations instead of dividends and mergers?

-

From a book I just read, here's some supportive evidence of this kind of thing happening: “Aducanumab is the first new drug to be approved for Alzheimer’s treatment in nearly twenty years. The FDA’s approval of aducanumab proved to be one of the most controversial in recent memory. Not only has the drug been considered to be clinically ineffective, a third of patients getting aducanumab suffered swelling or bleeding in the brain. Not a single member of the FDA expert advisory panel voted in favor of its approval, and three of the committee members resigned in protest, one calling it “probably the worst drug approval decision in recent US history.” The response from the scientific community may best be summed up by a commentary written by the head of the American Geriatrics Society titled, “My Head Just Exploded.…” Check out the whole fascinating saga in https://see.nf/aducanumab. A congressional investigation concluded the approval of aducanumab was “rife with irregularities,” raising “serious concerns about FDA’s lapses in protocol and [the drug company] Biogen’s disregard of efficacy. That didn’t stop the FDA from its 2023 accelerated approval of a similar antibody, lecanemab (Leqembi), of similar questionable efficacy and safety.” Excerpt From How Not to Age Michael Greger, M.D., FACLM

-

By the way, two side thoughts: (1) It'd be nice for TheCOBF to have an Amazon affiliate code, so that links to the books could generate a little extra $$ for the forum. https://affiliate-program.amazon.com/resource-center/how-to-build-amazon-affiliate-links?ac-ms-src=rc-home-card (2) Maybe we could have members submit favorite books for 2023 and vote/rank them?

-

I'm really liking this book. All about things that just don't change about human nature, and lots of anecdotes that investors will enjoy (about stocks, markets, economies, etc) Each chapter is about 11 minutes long (he says "You're welcome" for that, and I do appreciate it) I'm just 2/5 through it so far. It starts off with a new anecdote about Warren Buffett, and there are some good Charlie Munger quotes in here too. The opening story about Buffett: And, a quote I really enjoyed, by another investor Jim Grant: Morgan Housel wrote another book here in the forum, "The Psychology of Money", which I haven't read yet. Anybody else reading this one?

-

The Audible Plus catalog has Charlie's biography, "Damn Right!" so anyone can listen to it for free if you've got an Audible account at the Premium Plus level. I think I'm going to re-read my copy of Poor Charlie's too, this time with my almost-grown-up kids. They've been asking me about getting started with investing, and Charlie's generosity at mentoring others is making me feel ashamed that I haven't shared more about the topic, especially with them.

-

Buffett told CNBC’s Becky Quick in 2018. “Charlie has given me the ultimate gift that a person can give to somebody else. He’s made me a better person than I would have otherwise been. ... He’s given me a lot of good advice over time. ... I’ve lived a better life because of Charlie.” I've been trying to come up with some way to say how I feel about Charlie. Warren expressed it right there.

-

Page 56 in Poor Charlie's Almanack: "Faced with the choice between changing one's mind and proving there is no need to do so, almost everyone gets busy on the proof.» -John Kenneth Galbraith Charlie has developed an unusual additional attribute a willingness, even an eagerness, to identify and acknowledge his own mistakes and learn from them. As he once said, "If Berkshire has made a modest progress, a good deal of it is because Warren and I are very good at destroying our own best-loved ideas. Any year that you don't destroy one of your best-loved ideas is probably a wasted year." Charlie likes the analogy of looking at one's ideas and approaches as "tools." "When a better tool (idea or approach) comes along, what could be better than to swap it for your old, less useful tool? Warren and I routinely do this, but most people, as Galbraith says, forever cling to their old, less useful tools."

-

“This has been attributed co-Samuel Johnson. He said, in substance, that if an academic maintains in place an ignorance that can be easily removed with a little work, the conduct of the academic amounts to treachery. 'that was his word, "treachery." You can see why I love this stuff. He saves you have a duty if you're an academic to be as little of a klutz as you can possibly be, and, therefore, you have gotta keep grinding out of your system as much removable ignorance as you can remove.” ― Peter D. Kaufman, Poor Charlie's Almanack: The Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. Munger, Expanded Third Edition

-

https://beatyourgenes.org/2023/08/10/313-dr-lisle-nate-why-are-people-snobby-why-doesnt-my-spouse-want-to-improve-their-health-can-you-sleep-train-an-infant-single-by-choice-but-lonely/ Beat Your Genes podcast is about Evolutionary Psychology. I remember listening to this earlier this month, where Dr. Lisle answered a question about sleep training. Might have to skip past the first question if you're not interested in that one. In a nutshell: You won't screw up a kid by sleep training.

-

[ funny thought ] AI-driven customer service solutions? The first generations of these will likely make for some very funny customer stories. Imagine an AI chat bot giving customers incorrect answers, or arguing with customers like Sydney, and tell someone they are a bad customer and it was a good chat bot. I'm sure they'd have worked all those types of bugs out, but I can imagine some comedy gold will remain to be discovered. [ investing thought ] To my mind, it seems like the smart companies in these sectors could just as easily adapt to the new GTP landscape and pivot to the future where an LLM is baked into all kinds of software/services/apps.

-

Reminds me of the last 3 of the 6 phases of big projects: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Six_phases_of_a_big_project Unbounded enthusiasm, Total disillusionment, Panic, hysteria and overtime, Frantic search for the guilty, Punishment of the innocent, and Reward for the uninvolved. If this excerpt is too long for copyright, feel free to delete it. Last year I read "The War on The West" by Douglas Murray. These paragraphs from a chapter on reparations seemed like clear thinking to me: """ In 1969, the Holocaust survivor and celebrated postwar Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal published a work called The Sunflower: On the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness. It is an account of something that Wiesenthal says happened to him at the Lemberg concentration camp. In 1943, Wiesenthal was one of a group of forced laborers and one day is plucked from the line and taken to the bedside of a Nazi soldier who is dying. The man, called Karl S in the book, turns out to have joined the Hitler Youth and from there moved up the Nazi ranks all the way to the SS. During this time, he participated in one particular atrocity. He confesses to the Jewish man at his bedside that his unit had at one stage in the war destroyed a house in which there were around three hundred Jews. The SS unit had set the house on fire, and as the Jews inside tried to escape from the burning building, by leaping from the windows, Karl S and his comrades shot and killed them all. This is described in considerable detail, and if this was all The Sunflower was then it would simply be yet one more tale of the countless number of tales of Nazi atrocities carried out against Jews during World War II. But Wiesenthal’s book is not about that. It is about what happens next. Because it is clear that Karl has asked for a Jew to be brought to his bedside because he wants to confess to this crime in particular and to a Jew in particular, because he wants to get this particular atrocity off his chest before his imminent death. It is something in the way of a deathbed confession. And it is what happens next that makes Wiesenthal’s book so memorable. For after the SS soldier has finished his tale, and the reader perhaps expects some type of reconciliation, Wiesenthal gets up and leaves the room without saying a word. Later, Wiesenthal meditates on whether he did the right thing, and the second half of the book is given over to a symposium involving a range of thinkers and religious leaders who contributed their thoughts on the events that Wiesenthal has described. It is noticeable, incidentally, that many of the Christians who contributed to this symposium believed that Wiesenthal should have offered some kind of forgiveness to the soldier. But the broader consensus that emerges from the contributors is that Wiesenthal did the right thing. And if there is a reason that this comes down to, it is this: that Wiesenthal, although he was a Jew, like the soldier’s victims, had neither the right nor the ability to forgive the soldier for what he had done. In order for true forgiveness to occur, the parties involved must be not only the one who has done the wrong but the one to whom the wrong has been done. Wiesenthal may have been a Jew, like the victims, but he does not have the right to forgive on behalf of his fellow Jews who were gunned down by the soldier as they jumped from a burning building. Wiesenthal is not these men, women, and children. He is not even a close relative of these men, women, and children. These victims may never have wanted to forgive their killers. Perhaps they would have hated their killers forever and not wanted them to die in peace. The SS soldier had participated in such a terrible end for them, so what right did Wiesenthal have to say on behalf of all of these people that the SS soldier is forgiven? Why should the SS soldier die with even a part of his conscience cleared? After taking no care about the consciences of so many other human beings. Within this is a very powerful and important point almost totally lost in the debate about forgiveness in the modern world. In recent years, the prime ministers of countries including Australia, Canada, the United States, and Britain have all issued apologies for historic wrongs. Sometimes, as when the direct victims of these wrongs are still alive, this can ameliorate suffering and provide a form of closure for the victims. But when we are talking about apologies for things done centuries ago, we enter a different ethical territory. In such cases, neither the people claiming to be victims nor the people assuming the mantle of perpetrators are any such thing. When it comes to apologies for the slave trade or for colonialism, we are talking about political leaders and others making apologies for things that happened before they themselves were born. And apologizing to people who have not suffered these wrongs themselves, though some may be able to point to some disadvantage they can claim to have suffered as a result of these historic actions. Any apology begins to consist of people who may or may not be descended from people who may have done some historic wrong apologizing to people who may or may not be descended from people who had some wrong done to them. In the realm of reparations, this becomes messier still. For at this stage, the divide in the West is by no means clearly between victims and perpetrators. Whereas the governments in almost every non-Western country are strikingly ethnically homogenous (consider the political leadership in India, China, or South Africa), governments in every Western country are now made up of people of a wide variety of ethnic backgrounds. No Western cabinet would be able to work out the victim-oppressor divide even at the table around which they sit. Nor would any political party. Just consider the difficulty merely of working out what Elizabeth Warren may or may not be owed. The issue of reparations now comes down not to descendants of one group paying money to descendants of another group. Rather, it comes down to people who look like the people to whom a wrong was done in history receiving money from people who look like the people who may have done the wrong. It is hard to imagine anything more likely to rip apart a society than attempting a wealth transfer based on this principle. Perhaps that is why the difficult questions on this are ignored by everybody who has argued for reparations to occur. For instance, were any such scheme to operate in America, the country would have to carefully determine which racial groups in the country have been most harmed by American history. It may determine to limit the scope of its attentions solely to the issue of people who are the descendants of slaves. Though there is no reason why it should limit itself to that. But if it did, then the prelude to reparations would have to be the development of a societal, genetic database. It could be that this would only be necessary to create for the black population of the United States. It would then have to determine how to apportion the funds available. Anyone who thinks voter ID laws or vaccines are intrusive should prepare for the questions that will follow this process. For instance, after the genetic database is created, it will have to be decided whether or not the only recipients should be those who are 100 percent descended from slaves—if any such people can be identified. Should these people alone be given a full stipend? Should someone who is only descended from slaves on their mother’s side receive 50 percent of the same sum? Will the restitution process try to operate the “one-drop rule,” and if so, how will it ensure that nobody is taking advantage of the financial spigots that would result? And, of course, all of this would be predicated on the idea that a vast wealth transfer from one racial group to another racial group in America in the 2020s will bring racial harmony and will not cause any igniting or resurgence of racial ill feeling. Can anyone be sure that this is the most likely result? Only around 14 percent of the US population is black. As of 2019 more than half of that population (59 percent) were millennials or younger (that is, under the age of thirty-eight).9 During their lifetime, it has been illegal to treat people differently because of their skin color. Jim Crow laws were decades in the past before this group was born. The official prohibition on the further importing of slaves into the United States had been signed two centuries before this group was born. To begin to apply reparations to this community would require a clear differentiation between black Americans who are descendants of Africans brought forcibly to the United States and black Americans whose ancestors voluntarily came to the United States in the centuries after slavery was abolished. And what about the people doing the paying? There will be many people who have come to America’s shores since slavery ended—most of America’s Jewish, Asian, and Indian populations, for instance—who may make an objection at this point. Why should those whose ancestors played no part in a wrong be made to forfeit a part of their tax dollars in paying for something that happened generations before their family came to America? Should people whose ancestors died in the Civil War fighting for the North get any special dispensation? Should those whose ancestors fought for the South pay disproportionately more? There are very obvious reasons why people might call for reparations: for political convenience or in genuinely seeking to right a historic wrong. But there is an equally obvious reason why they can almost never be drawn into giving any details of what the process might look like. That is because it is an organizational and ethical nightmare. We also know that no matter how much is done to address the issue it will never be enough. We know this not least because Britain’s attempt to make up for the slave trade is over two centuries in the past and the issue of further reparations being made is still raised. Indeed, the subject is discussed as though critics either do not know or know and do not care how many resources Britain poured into abolishing slavery in the 1800s. The British taxpayer paid a hefty price for the abolition of the slave trade for almost half a century. And it has been proven that British taxpayers spent almost as much suppressing the slave trade for forty-seven years as the country profited from it in the half century before slavery was abolished. Meaning that the costs to the taxpayer of abolition in the nineteenth century were almost certainly greater than the benefits that came in the eighteenth century. The British government of the day spent 40 percent of the entire national budget to buy freedom for the people who had been enslaved. At the time, the only way that the British government could get the consensus needed to abolish the trade was to compensate those companies that had lost income because of the trade. This sum was so large that it was not finally paid off until 2015. And while some campaigners have used this to show how recent the trade in human beings was, it rather better exemplifies the unprecedented lengths the government was willing to go to in order to end this vile trade. Two of the scholars who have done some of the complex math required here have estimated that the cost of abolition to British society was just under 2 percent of national income. And that was the case for sixty years (from 1808 to 1867). Factoring in the principal costs and the secondary costs (for instance, the higher prices for goods that the British had to pay throughout this period), Britain’s suppression of the Atlantic slave trade, it has been claimed, constituted “the most expensive example” of international moral action “recorded in modern history.”10 Several things could be learned from this. But one thing worth noting is that such actions appear in the current era to be almost entirely unknown. What is more, they appear to buy Britain—and the wider West—absolutely no time off in the purgatory of the present. The British may have actually overpaid in compensation for their involvement in the slave trade, but it appears to count as nothing; demands for reparations internationally and domestically still continue. Is there any end to this? Are there even any means to an end to this? The British precedent suggests not. If America were to find a way to pay reparations today, why would the same demands not re-arise two centuries later, as they have done in relation to Britain? If the great reparations machine were to pour out money, why should it be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity? It is not a problem that is unique to the British or American examples. Whenever a country such as Greece gets into financial trouble, politicians there can always be found who are willing to say that Germany must pay Greece for its occupation of the country during World War II. Indeed, Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras made precisely this demand again in 2015. There are not many ways to see how this would stop. Other than Greece never getting into financial difficulties ever again. The same applies to the payment of reparations for empire or slavery. It will always be the case that there will be African politicians who will claim that the problems of their country are not to do with any mismanagement of their own, but because of colonialism. The late Robert Mugabe was a fine example of this genre. The only way for such demands to stop would be for every former colony to be thriving and well run for the rest of time with governments that are always and everywhere strangers to corruption. Likewise, in the American context, what would it look like for reparations to have been paid off? Even writers, such as Coates, who have argued for reparations have joked about the likely consequences of doling out large sums of money to black Americans. Dave Chapelle did a skit on this, showing black people spending their reparations payments on fancy cars, rims, clothes, and more. It would be a good time to buy shares in Nike. But the serious fact is that it could only be deemed that reparations had worked if black Americans either performed equally to or actually outperformed all other racial groups. And not just in the aftermath of payments but for every year in the foreseeable future. If black Americans underperformed, then it could always be argued that reparations had not so far adequately occurred because inequalities still existed. In order for demands for reparations to go away, any and all wealth disparities would have to disappear not just once but forever. Until then, it is hard to see how the demands for financial compensation will be able to stop. In the meantime, it is impossible not to note how fantastically one-sided, ill-informed, and hostile this debate has become. No world forum ever concentrates seriously on any form of reparations that does not involve the West. And there is an obvious reason why there are no calls for reparations to Africans abducted into the slave trade that went East. Which is that the Arabs deliberately killed off the millions of Africans they bought. But there is little explanation as to why it is that today it is only Western former colonial powers or former slave-owning countries that are expected to pay any sort of compensation for sins of two centuries ago. Modern Turkey is not expected to pay money for the activities of the Ottoman Empire. An empire that, incidentally, ran on for twice as long as the empires of Europe did. After all these years, it is still only the sins of the West that the world—including much of the West—wish to linger over. It is as though when looking at the many, multivariant problems that exist in the world, a single patina of answers has been provided that is meant to explain every problem and provide every answer. """ Excerpt From The War on the West Douglas Murray