maybe4less

Member-

Posts

211 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Everything posted by maybe4less

-

It looks like any company with an East Asian supply chain is going to have it disrupted for probably a couple quarters. Most companies should be able to survive that, but there have to be some that are overlevered, have debt due soon, or some other issue that will make it hard to avoid financial distress. Does anyone have any good short ideas along these lines?

-

If you use Google Finance, now might be the time to...

maybe4less replied to Liberty's topic in General Discussion

Source of this information? Thanks Why would they need to take down the old one to build a new one? -

Thank you! What I am looking for for larger orders is that they can fill some, wait for a bit, and fill more, wait a bit, and fill more. Do you see that happening when you have adaptive order? The other question I have is, do you know if they reset their scan time when bid/ask moves? If that’s the case then the order may never get filled when bid/ask is constantly changing. Lastly, I noticed a much higher chance to be filled in NYSE when using this order type. Not sure if I have enough data sample to prove that though. Yeah, the behavior of filling some and waiting and then filling some more is what I typically see with the adaptive orders. Sometimes if the price puts my limit "in the money" I will start getting fills in quick succession. Not always but sometimes (sometimes my limit will be below the bid/above the ask and the algo won't get me a fill for a while). When it doesn't happen, I usually adjust my limit price to slow it down, unless I am eager to get shares. I think they must reset the parameters depending on price moves, volume, etc, but I don't know exactly what they do. Never compared the different exchanges with the algo.

-

Thank you! I tried the adaptive algo for a while and found that sometimes as IB is scanning between bid and ask, stock starts to move up without me getting any fill. I wonder if it is moving because IB is scanning and detected by other HFTs, or if it is just coincidence. Have you experienced this? Sometimes IB scans and fills a portion of my order and scans again and fills another portion later. Have you seen them doing this? This sometimes happens with smaller and less liquid stocks on the "normal" urgency setting. When I switch to "patient" urgency I don't drive the stock up. I think no matter what though you have to be patient with large orders if you want to avoid moving the market.

-

In my experience with lightly traded stocks, a limit order at the ask will only fill 100 shares and then the bid will move to one penny over your limit order which is of course why market orders are good to use when filling the order is more important than scalping a couple pennies. Buth then, a market order can really stick you with some bad fills, hence the allure of the adaptive algo, but alas it has its problems too. Ain't no such thing as a free lunch... Free trades at Merrill Edge are nice because you can split your order into multiple orders for free (assuming you are within your monthly allotment of free trades). But then Merrill won't trade many low price/volume stocks anymore. Years ago, I absolutely never used market orders, but over the past 10 years, I find sometimes they are just the only way to get a fill. Yep, but the most annoying trades are those where your bid never gets a fill, but then you see a trade for 0.01 penny higher a microsecond later. While you can only trade in 1 penny increments some HF trade can do smaller increments and suck up all the liquidity. At least that’s my take of it. FWIW, I use IB's adaptive algo all the time for all kinds of stocks and get great fills. For most stocks I use it on normal urgency and more illiquid stuff I used the patient setting. Merrill's free trades are nice, but the execution is the worst of all the brokers I use (Schwab, TD, Fidelity, IB, and Merrill). Which broker do you think has the best execution? I've tried out TD, Fido and IB. Initially I have my bigger account in IB and it usually has worse fill, but after I moved the account to TD, I notice bigger accounts have worse fills in general. I see the same behavior of getting a small partial fill and price moves up. That experience of having a small partial fill and then seeing the price move up is why I like IB's adaptive algo so much. It simply hasn't happened to me with the algo. Of the others that I've tried, it seems like Fidelity might have the best execution, even for larger accounts.

-

In my experience with lightly traded stocks, a limit order at the ask will only fill 100 shares and then the bid will move to one penny over your limit order which is of course why market orders are good to use when filling the order is more important than scalping a couple pennies. Buth then, a market order can really stick you with some bad fills, hence the allure of the adaptive algo, but alas it has its problems too. Ain't no such thing as a free lunch... Free trades at Merrill Edge are nice because you can split your order into multiple orders for free (assuming you are within your monthly allotment of free trades). But then Merrill won't trade many low price/volume stocks anymore. Years ago, I absolutely never used market orders, but over the past 10 years, I find sometimes they are just the only way to get a fill. Yep, but the most annoying trades are those where your bid never gets a fill, but then you see a trade for 0.01 penny higher a microsecond later. While you can only trade in 1 penny increments some HF trade can do smaller increments and suck up all the liquidity. At least that’s my take of it. FWIW, I use IB's adaptive algo all the time for all kinds of stocks and get great fills. For most stocks I use it on normal urgency and more illiquid stuff I used the patient setting. Merrill's free trades are nice, but the execution is the worst of all the brokers I use (Schwab, TD, Fidelity, IB, and Merrill).

-

It's outside the feds circle of competence too. Interests rates, the time value of money, are a market phenomenon. You might as well have a government board set the daily price of Avocados. Can I ask your opinion on the Fed slashing interest rates in the 2009-2013 period. This was most certainly not a market phenomenon, as credit was drying up. The Fed's action essentially re-started the US economy and prevented a depression. Beautiful deleveraging and all that. Do you think they were wrong, or lucky, or something else? It was a market phenomenon. The demand for risk-free assets soared, pushing down interest rates. The Fed was following/supporting that.

-

This is correct - so obviously correct, in fact, that I would be absolutely shocked if the Fed got this wrong... Yeah, fair enough. As others have posted the Fed seems to have done a very good job through the crisis and since. However, I think this is the market's concern as evidenced by the flat/inverted short-end of the curve (i.e., that they will have to reverse some of the planned rate hikes in the near-term). I can see the point too. The Fed is being fairly aggressive despite the short-term nature of the stimulus, so why not pause a bit and see how the economy develops? However, I'm not smart enough to say which is right, let alone that the Fed is definitely making a mistake.

-

As long as those tax rates stay in place, yes the increased value is "permanent." However, I'm talking about GDP growth. Cutting taxes gives a boost to GDP growth (not GDP level) that is transitory. Which I agree in macro terms is important, but when I look at specific portfolio companies, it really isn't. If I own FRP, and their income consists of lease revenue, interest income, and cash from the rock pits... let's say all of this stays the same, just to keep things simple. At 22% tax rate the company is now significantly more valuable, even with the same figures as last year, when paying 35%. You can look at different figures, but simplistically, you should be throwing a multiple onto that incremental income, and the value of the company should be higher. The markets right now in a lot of cases are saying the opposite. People have essentially fabricated the recession narrative out of nothing, and what I'm saying is that even if it were true(to the extent that is reasonable, ie not a crisis) it doesn't in many, many instances, with a lot of companies, support lower equity prices. I don't disagree with you. I was making a different point about why the Fed might be in danger of making a policy mistake.

-

As long as those tax rates stay in place, yes the increased value is "permanent." However, I'm talking about GDP growth. Cutting taxes gives a boost to GDP growth (not GDP level) that is transitory.

-

I don't disagree with your bullishness, but tax cuts are definitely a one time boost to growth. The rate of change is more important than the level and we aren't getting a tax cut every year.

-

Totally agree with this. I would add that it seems tax reform is one time stimulus that has juiced growth this year, such that some of the headline strength this year may prove ephemeral. It appears that the Fed might not be taking this into account and that there is therefore a meaningful risk of a policy error. I think we are seeing this concern reflected in the flattening or "inversion" at the front end of the curve. Ignore those complaining that the Fed doesn't care enough about the stock market, but I think serious market participants should be concerned about the Fed mistaking temporary strength for something persistent that they need to get ahead of.

-

Yes, just like mutual funds, ETFs sometimes have to make distributions to shareholders. Information is given to you that tells you which portion is short-term and which is long-term. Thank you! In this case, what would be the reason for a manager to create an active ETF instead of a mutual fund? I remember Peter Lynch saying it is bad idea to buy any mutual funds near the end of the year, because investors won't get the distributions but have to bear the tax on the capital gain. Does the same apply for active ETF? Because ETFs are getting inflows and mutual funds are not :) It would depend on the particular active ETF, but if it was sitting on unrealized gains and then got outflows during the year, you might expect a similar dynamic to play out with the capital gains distributions.

-

Yes, just like mutual funds, ETFs sometimes have to make distributions to shareholders. Information is given to you that tells you which portion is short-term and which is long-term.

-

How is a REIT shareholder taxed for US investors?

maybe4less replied to muscleman's topic in General Discussion

Yes, that's true, but generally if your position is not huge and you hold it briefly, you'll show no income on the K-1 and then there is nothing to report on your taxes. -

Over the past 10 years, I've seen two kinds of collapses. First is sky high valuation followed by disillusioned shareholders. Second is stock moving lower first, and value investors screaming bargain all the way down, while E continues to deteriorate. I think AAPL is in the second basket. The problem with valuation with P/E is that you have to be damn sure that E is going to go up, not down. AAPL is changing reporting standards. That's a tip off that the next few Es will be bad. No opinion on whether Apple is this second kind of stock or not, but the comparison to Cisco in 2000 is just ridiculous. I think even Apple bears would find it so. Two totally different situations and valuations.

-

How is a REIT shareholder taxed for US investors?

maybe4less replied to muscleman's topic in General Discussion

You don't get K-1s from REITs. The experience for a US investor owning REITs is like that of owning any other "normal" business. The REIT itself generlaly just doesn't pay taxes as long as it follows IRS rules. -

Thanks for your response. In all frankness, the graph you provide could be interpreted in so many ways… If you add another layer about expected expectations it would even be possible to take the modern monetary theory seriously. :) I will follow you in this rabbit hole and then try to provide perspective. Maybe it's my scientific background bias and expectation that 2+2 usually gives 4 but if 1-easing was used to prevent real interest rates from falling too low and 2-easing eventually caused a "big pop" (more on that later in the perspective), then why tightening has been accompanied by increasing real rates? Why doing opposite things cause the same result? There are a huge number of potential answers and I suspect which one you will come up with. ;) In terms of perspective (looking outside of the time frame of your graph), real interest rates (which are tied to potential GDP growth) have been convincingly coming down since the early 80's (not only in the US BTW) and this is for another thread to discuss but the blips we have seen in the last few years have not changed that trend unless one believes that the times they are changin'. I try to supplement posts with factual or corroborating evidence and I could have supplied you with solid work that contains however derogatory comments but here's one from the Master himself: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/ben-bernanke/2015/03/30/why-are-interest-rates-so-low/ Look, he says, I did what I could and it's up to the other actors to play their role. One of the things that bothers me is the comment, which I agree with, that punctual government spending could cause a short term increase in real interest rates. Mr. Bernanke made those comments in 2015 and perhaps did not envision that the recent administration would put the pedal to the metal in terms of government spending and fiscal deficits in a late cycle. The major thing that bothers me though is that this easing program was to give time to the powers that be to deal with the secular forces and to allow a "beautiful" deleveraging. Deleveraging, what deleveraging? As I sip my coffee in late 2018, we are, on a net basis, on more shaky grouds for debt especially at the public and corporate (hypertrophied BBBs, leveraged loans, high yield etc) levels than 10 years ago. And now we are "ready" for tightening? Sorry long post. Maybe4less, you seem to have an interest in maturity transformation. For a historical parallel, alchemists involved in metal transformation (they called it transmutation then) used the scientific fact related to the differential density of lead and gold. Gold creation was a myth but alchemy was both practice and philosophy. Have you taken a look at which end of the curve the Treasury is selling its debt issues? There is an obvious connection to monetary easing (or absence thereof) as the fiscal/monetary firewall is being tested. An interesting side effect of the tightening mode is that the Fed has been (and will be more and more?) absent from government auctions and, even if the supply of government debt has considerably increased lately, the Treasury, in its great wiseness, has preferentially and to a large extent gone for the 2 year-auctions versus the 10 year-auctions: YTD: 2yr + 55%, 10yr +26% thereby conducting the equivalent of a fiscal operation twist. In my humble experience, for the typical firm with rising debt, short term refinancing may be an ominous sign but I'm just a guy paying his bills every month. Interesting times. As I suggested in an early post, the Fed takes its cues from the state of the economy and financial markets. It is a follower, not a leader. Rising real rates have caused the Fed to reduce its level of accommodation. If we aren't "ready" for a tightening, than the Fed can only try to help to contain the damage (traditionally by lending to solvent financial firms that have a liquidity issue). But this is just how the credit cycle works: debts build up and towards the end of the cycle interest rates rise. The Fed couldn't stop it if it wanted to. The idea that the Fed can control long rates given the size of the US (and global) economy doesn't really make too much sense from a theoretical standpoint as Bernanke explains himself in that article you reference. He describes a system where the Fed tries to determine what equilibrium real rate is and then uses its tools to target the money supply consistent with that equilibrium rate and its inflation target. It also doesn't make too much sense empirically, as "anti-market" government policies (e.g., currency pegs, price controls, etc.) have inevitably failed throughout history. Apologies if it seems like I'm ignoring your other points. I either didn't understand them or they seemed off-topic. Circle back if there are any in particular you'd like to dig into. I will, however, point out on the deleveraging issue is that it was a deleveraging of the private sector (primarily households), not of the public sector. The US largely swapped private debt for public debt.

-

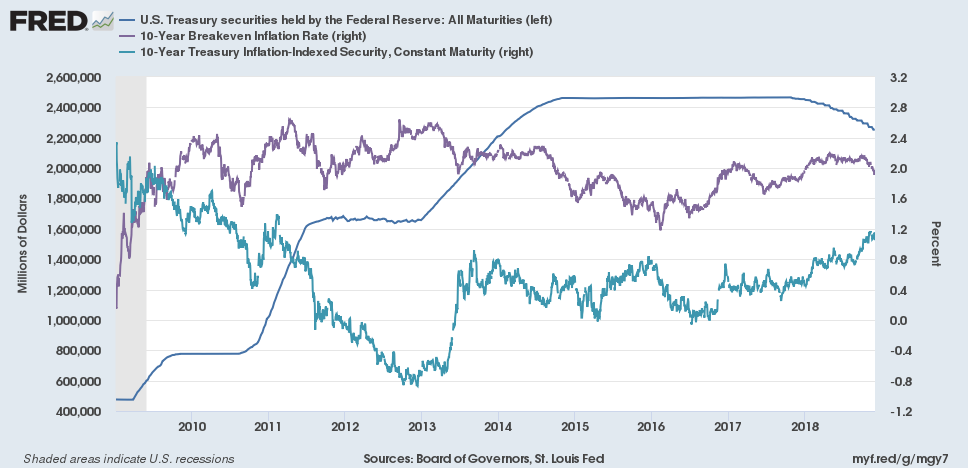

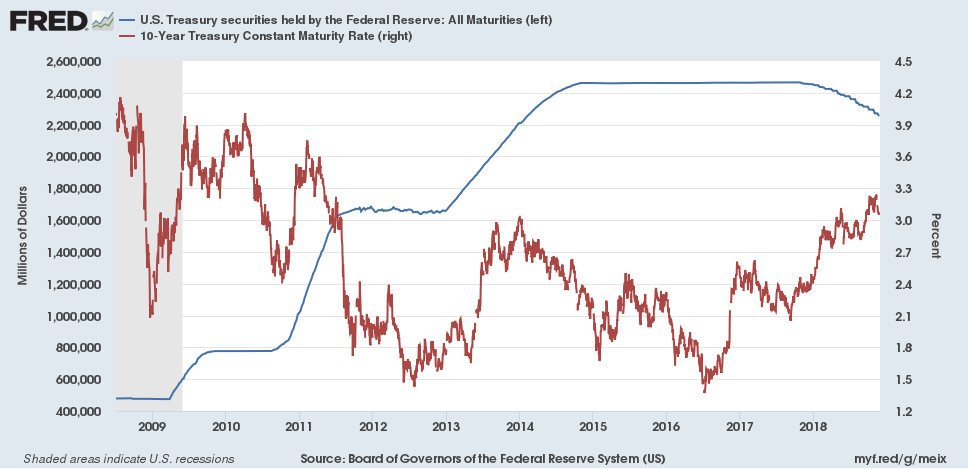

Many ways to assess this and the picture remains fuzzy. One of the difficulties is that the central banks try to control the message and the message has evolved during the QE process as rationalization to initiate and repeat the rounds has radically changed and in the end Mr. Bernanke said: "The problem with quantitative easing is that it works in practice, but it doesn’t work in theory”. :o The inflation expectations aspect is interesting in theory but does not fit the data. If you look at different graphs with inflation expectations and chronologically match with the CB balance sheet, you see that the initial QE (announced end 2008) was associated with rising inflation expectations but it is not clear if there was any cause and effect (inflation expectations recovered just like after the 2001 recession when QE was discussed only in ivory towers). With QE2, there was, with some measures, a temporary spike in inflation expectations but the there was a relatively rapid return to longer term trends. With QE3, there was no positive correlation as inflation expectations diverged and continued to trend lower, a trend that has mostly continued to this day... In my free time, I look at firms in distress. A common feature is that, initially, debt can be used to meet an "unexpected" problem. Then debt can be augmented to deal with lingering issues with no net positive effect and there arrives a point when more debt is counter-productive (for firms that cannot print their own currency, there may be an acceleration here). A classic case of diminishing returns (digging yourself in a hole). It seems to me that the central bankers realized that additional rounds of QE were simply not effective because the system was flush with excess reserves and because, effectively, of the the liquidity trap that you describe without naming it. The way to deal with this may have been to come upfront about it but, for obvious reasons, the CB came out with the rational that a deflationary spiral had been avoided. The big question I have is: was it avoided or simply postponed? A potential interpretation of yesterday's wording may be that there is more postponing in store. Mr Bernanke, when explaining the evolving rationale behind QE often mentioned the risk of losing public confidence and I wonder if that risk has not been underestimated. Contrarian opinion: The emperor has no clothes. Potential personal bias: tendency to overestimate lag effects. "Clearly there is something else going on." You bet. I hope this discussion continues but I have reached my diminishing return level of contribution for this topic. I think it's important to reiterate that interest rates are made up of two components: inflation expectations AND real return expectations. I don't disagree with your analysis of inflation expectations versus the Fed's balance sheet. But real rates started dropping towards the end of QE1 and continued to drop (with some small bumps) straight through QE2, even though inflation expectations increased. (That the spikes in both inflation expectations and real rates during QE2 were transitory is why we got QE3.) Inflation expectations didn't move all that meaningfully after QE3, but we got a big pop in real rates that has persisted. (See attached chart.) The relative stability subsequent to QE3 in both inflation expectations and real rates is likely why the FED has not felt that QE4 was necessary.

-

Interesting. We could "fight" back and forth with graphs forever and run into circular arguments but did you consider that whatever effects are produced by what the Fed does or is expected to do happens with a lag? What about what is going on now as we see the early effects of tightening (opposite of easing): are interest rates going down? I mean I guess it is possible, but it's really hard to understand what such a lagged effect is on interest rates from the data we have. If you look at the three post-crisis expansions of the Fed's balance sheet, rates either went up the entire time they were buying or went up and were flat almost the entire time they were buying. Is our hypothesis that rates don't really start going down until they've finished buying Treasuries? If your model for why interest rates should go down when the Fed is buying is based on a supply and demand model, then I don't think it really makes sense to consider such a hypothesis. Clearly there is something else going on. To address your specific question about whether rates are going up as the Fed shrinks their balance sheet. No, they aren't, but as JimBowerman implied, inflation expectations are not low. Instead, the Fed is responding to a stronger economy and a lower demand for short-duration assets by raising rates and shrinking its balance sheet. Interest rates are determined by expectations for real growth and for inflation. The Fed is simply led by and reacts to the economy and the financial markets. (E.g., see Powell giving dovish comments this week after global growth forecasts have been revised downward and risk-assets have declined in price). Another way to think about QE is that it was meant to to keep SHORT-TERM rates UP. The Fed was losing control of short-rates during the depths of the crisis due to the great demand for and the resultant scarcity of short-term safe assets. By providing more short-term safe assets, they alleviated the scarcity of safe short-duration assets and the pressure for such assets to appreciate in price, helping to stabilize the financial system and prevent further deflationary impulses. This is also why they started paying interest on excess reserves: in order to regain control over the front-end and establish a floor for short-term rates. They used to manage the front end with the the Fed Funds Rate, but it had lost its effect due to the Fed Funds market becoming essentially defunct since all the banks had all the reserves they could ever need due to QE.

-

Yes, this is exactly right. The best way to think of QE is as a mechanism of maturity transformation. There was an incredible demand for short-maturity safe assets that was driving interest rates lower. The Fed traded its short-duration excess reserves to the private sector in exchange for longer-duration assets (mostly Treasuries an Agency MBS). If you overlay the chart of the Fed's balance sheet and interest rates, you can see that the initiation of a new round of QE was always accompanied by an INCREASE in interest rates (In the attached I'm showing the 10-year). I think most people get the direction of causation wrong. The Fed increased its QE efforts when it felt that interest rates were getting too low and therefore deflationary pressures were getting too high. (Link to graph here as well: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=meit)

-

It just cancels out. It's all digital. Am I right that this interest payment is the drain on liquidity from the economy? In addition to remitting profits to the Treasury to cancel out these interest payments, they also pay interest to banks on excess reserves. Whether the banks do anything with those increased excess reserves is another story.

-

It just cancels out. It's all digital.

-

Less sugar and less alcohol. The latter is more important for your headaches probably. :)

-

I know FED uses the new cash to buy treasury bills, which means treasury will have more liabilities. But how will that also be liability for the FED? When the Fed creates cash to buy bills, that cash is registered as a liability. It's simple double-entry accounting. The asset needs an offsetting liability.