rb

-

Posts

4,182 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Posts posted by rb

-

-

More WFC

-

If you're thinking in terms of weapons procurement and maintenance for Saudi Arabia than the names are BAE, Rolls Royce and Boeing.

-

Why did you waste some many words? You could have just said, "I'm smarter than everyone." Are you an economist?

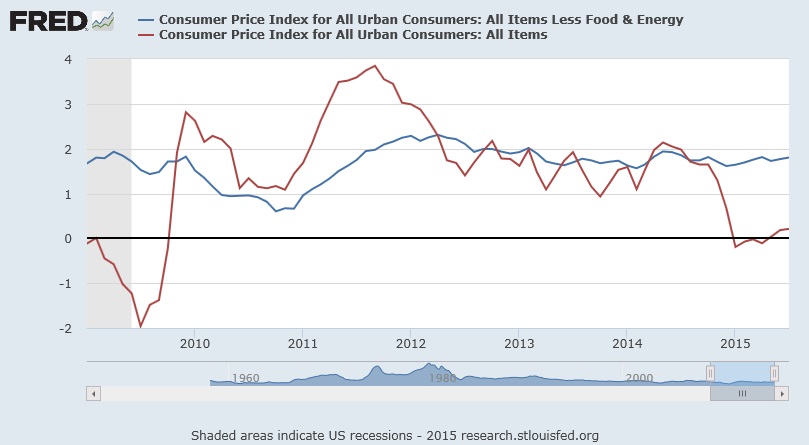

My point was there has been no, "slow overall deleveraging". We already have deflation for everything in the CPI less shelter, see attached. No massive changes changes needed.

Kevin,

As a matter of fact I am an economist. I don't know why that's relevant though. I also didn't say I was smarter than everyone, I was just addressing the points you brought up.

You keep saying that there has not been any slow deleveraging when the data points otherwise. You claim deflation is everywhere. It's only shelter you say, but really it's commodities that caused the negative print in 2014. See my attached graph. The thing is that inflation is a rate of change so in order to keep getting that print you need for commodities to keep dropping. There is a reason why all the central banks in the world use core cpi (cpi less food and energy) for policy decision instead of cpi.

-

RB do you believe that US has decoupled from the rest of the world?

If not, with inflation where it is, do you think it is possible that inflation could drop a bit lower? What if we have a recession at the same time? I do not know the answers to these and thus, cannot make a case.

Things can change quickly as it has been a while since the last slow down. I do not see what I lose by being cautious and prepared.

Wisdom,

I'm not saying that we cannot have a slow down or even a recession. It doesn't look like it's imminent, but no one knows these things. I'm also not saying that inflation may not drop from current level if something like that happens. Also I'm not one of those people that sees inflation around every corner. In fact I think that we'll be in a low inflation environment for a long time. What I'm saying is that there is a very big difference between disinflation and deflation. That zero barrier is very significant like the sound or gravity. The closer you get to it the harder it is to advance towards it. To fly you only need a small Cessna. To go into space you need a space ship.

The US also hasn't decoupled from the rest of the world more than in the past. What I was trying to convey is that the foreign sector of the US economy is not as large as for other economies. So to put it in your words I would say that the US economy is more decoupled from the rest of the world than the rest of the world is coupled to the US. Actually the way that external shocks make their way into the US is through the financial system, not through the real economy. It's true that if it's not ring fenced troubles of the financial system will make their way into the real economy but that's a whole different conversation.

Also to address your earlier post about household debt and revision to the mean. US household debt to gdp went from 98% in 2009 to 80% now. That's a large decrease. I couldn't quickly find a long term series for household debt to GDP, but from memory the long term average is lower but not much lower - around 50-60%. I think that household delevering in the US will still go on but we're probably not far from the end. You also have to keep in mind supply and demand for credit. The cost of credit (interest rates) are also lower than long term average so you should probably expect the that the equilibrium for levels of debt should also be higher than historical levels.

-

So you're saying that Japan's deflation was due to demographics and totally non-related to the real estate/equity bubble that bursted in the early 1990s? What about the deflation in the U.S. after the Great Depression?

I don't know who we can look at the trillions spent globally in fiscal and monetary stimulus, which has failed to produce any respectable amount of GDP or inflation growth, and then determine that there is absolutely no deflationary threat or support for Prem's thesis.

Then add to that the commodities are crashing. Bond yields are cratering and were at substantially negative levels just a few months back in certain European countries. Global GDP growth is slowing. The debt overhang for the developed world is massive. And despite a tightening labor market, no sustained growth in real wages has yet occurred. Somehow, we're supposed to look at all of this information and determine that deflationary fears or totally unsupported?

Maybe I'm a fear-mongerer, but it certainly seems to me that the data is showing that deflation is, and has been, the predominant threat since 2009 and that the inflationary story has been BS. The creation of credit is inflationary. The unwinding of credit is deflationary. I don't know if we're into that unwinding phase yet, but when we get there you can be guaranteed that it will be deflationary with, or without, an economic shock. Considering that the globe as a whole is carrying unprecedented amounts of debt, it could certainly be a very prolonged period. Don't fail to see the forest for the trees.

Also btw, I don't know why Japan is relevant here? Fairfax doesn't have Japanese deflation hedges and the Japanese economy is very different from the western economies on which Fairfax has deflation hedgesI would actually say that Japan is very similar to many European countries with poor demographics, birth rates, high debt, low-growth, export driven, etc. etc. etc.

Two Cities, as promised, I'm coming back to you with some delay.

You bring up a lot of points so I'm going to try to address it as much as I can. So let's begin with Japan. It's harder for me to do a very deep dive with numbers on Japan because I don't have much access to Japan stats so please excuse me if I stay a bit high level. The similarities between Japan and the US are that they had real estate bubbles (in Japan it was commercial RE in the US was all RE) and that a lot of risk related to that was concentrated in the financial system. That's kind of where similarities end.

Japan's households are prodigious savers that's why Japan is dependent on exports. US households are prodigious consumers and got levered up. In the US households were levered up, in Japan corporates levered up. In the US you had trade deficits, in Japan you had big trade surpluses. In the US the government moved to clean up the banking system, in Japan you had zombie banks. I could go on but I'm starting to sound like George Carlin.

Japan had an issue where the corporates behaved like households instead of corporates, cutting investments and hoarding cash instead of issuing equity when trying to delever. Add to that the fact that they had new and fierce competition in their export markets from Korea, China and other players and you get a massive deficit in demand. The households did not step in to fill that demand gap because over there they're savers not consumers so you end up with a huge output gap and deflation. Demographics played a part too mainly on the domestic consumption side. But I'm not sure that if Japan had better demographics things would have been different. Domestic consumption over there is and has been very weak.

As you can see about the only comparison between Japan and the western economies is that they've had a bubble too. you mention the European economies that are export driven, bad demographics, high debt, etc. The European economy that comes closes to Japan is Germany and they didn't have a real estate bubble and the debt isn't very high.

Bond yields are cratering in some European countries: of note are Germany, France, Netherlands and Finland. These have more to do with the Euro crisis than inflation expectations. Basically Italians, Spaniards, and Greeks would rather have German, French, and Dutch euros rather than their own. They're willing to pay for that.

Further on, slowing GDP growth doesn't mean deflation, the sign of a tight labour market is inflation - so you don't have a tight labour market. Debt overhang leads to deflation if you have an uncontrolled deleveraging - the US has delivered a lot in a controlled way. Could it have been handled better? Yes. Is the risk much much lower today than in 08? Hell yes!

You bring up the US deflation of the 1930s. Back then the US was on the gold standard, it had a high interest rate environment in the midst of a massive economic contraction and it was running budget surpluses. Does that sound like the situation we're in today?

I'm not saying that high inflation is around the corner. I'm just saying that deflation is far away. Yes the creation of credit is inflationary and the reduction deflationary. But you have had a lot of credit reduction in the US with the government stepping in and closing that output gap with it's own credit. Also right now the US fiscal position looks pretty good. You will probably see US budget surpluses when the economy gets to full employment.

So to argue that we're at risk for inflation you have to make an economic case that there will be such a dramatic drop in demand (the kind that results in 20% unemployment or something like that) or that the US government will be forced to undergo a significant uncontrolled delevering at the sovereign level. I don't see that even remotely happening. But if you do, please make the case.

-

What behaviour changed? People stopped taking on debt?

Yes. Household debt is significantly below pre crisis levels. At least in the US. Didn't check all of Europe.

As I have said before. This statistic in isolation is a waste of time. Total debt to whatever income measure you want has increased not decreased since the last financial crisis. Only the US, UK, Spain and Ireland have experienced household deleveraging. The McKinsey study shows 80% of countries have higher household debt. Some quotes from the study:

Seven years after the global financial crisis, no major economy and only five developing ones have reduced the ratio of debt to GDP (Exhibit 2). In contrast, 14 countries have increased total debt-to-GDP ratios by more than 50 percentage points.

Which countries have deleveraged since the last crisis? Israel, Romania, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Argentina.

The fact that there has been very little deleveraging around the world since 2007 is cause for concern. A growing body of evidence shows that economic growth prospects for countries with very high levels of debt are diminished. High levels of debt—whether government or private-sector—are associated with slower GDP growth in the long term, and highly indebted countries are also more likely to experience severe and lengthy downturns in the event of a crisis, as consumption and business investment plunge.10 Indeed, the latest research demonstrates how high levels of debt lead to a vicious cycle of falling consumption and employment, causing long and deep recessions.

Kevin, I've engaged with you on another thread where you were talking about a lot of different things at once. I told you that if you want to explore any of them in particular based on economic concepts I'd be glad to go into them with you. You didn't reply.

In that topic you've also referenced this McKinsey paper. It is at best a lazy paper and at worst dishonest. In it they constantly mix up rates and levels of debt. A total no-no. Also the concept that they use that higher levels of debt lead to the vicious cycle of lower economic growth and higher unemployment comes from a Reinhart & Rogoff paper that has been discredited in a very embarrassing way when it was proven that their math was wrong which led them to confuse causality with correlation.

Over here I was talking about the FFH deflation hedges that apply to US and EU, not globally. If you're going to make an economic argument for deflation you should explain how we are at risk of a massive decrease in demand or a massive increase in supply that will break sticky prices and put those economies in deflation.

By the way, a very slow overall deleveraging with the government levering up to offset private sector delevering is key to avoid deflation. So what exactly is your point?

-

I'm actually thinking the figures are quite accurate except unknown what the cost of float is taken at.

Berkshire does have a return on invested capital to a new investor at current prices of no more than 15%.

It also has some debt, minus the almost "Free float", plus a premium to the assumed rate of the long bond for desired equity risk premium. The differential is positive if you assume this and that the quality of the earnings demand a discounting not much more than 4 or 5%. Still, I'm not entirely sure what this means. Looking at the big picture, it does seem we shouldn't expect a shareholder to earn more than 8-15% per year at current prices. That's a broad range, let's call it pessimistic to optimistic scenarios.

Sorpion,

I'm a bit confused by your post. Why would Berkshire's ROIC depend on shareholders or when one bought the shares?

I also don't see how one can agree with the numbers. I was particularly questioning their WACC number. I did not think I'd engage in a discussion based on CAPM on a value investing board, but here we go.

Let's drop the decimals and assume for simplicity that inflation and 10-year yield are 2%. So let's look at the cost of equity (Ke) for Berkshire.

CAPM says something like Ke=10yr Yield + beta(BRK)*MRP. Now MRP is generally 5% and I'm not gonna go and check but I think it's a safe assumption that BRKs beta is less than 1 but let's say 1. That would imply Ke(BRK)=7%.

Another way to look at it is that long term the stock market returns about 6% real so that would imply a cost of equity of 8%.

So all this would imply that BRK's cost of equity is somewhere between 7% and 8%. Now besides equity BRK has a bunch of debt and float and all that and that's lower cost financing than equity. So if it's cost of equity is at most 8% how do these clowns get 8.7% WACC? How is that figure accurate?

As for your statement that BRK is to return a range of 8-15% going forward, based on the figures above that would mean that BRK is at best severely undervalued or at worst fairly valued. I fail to see the value destruction.

-

Two cities, I will get back on your points later on tonight. Bit busy right now.

-

What behaviour changed? People stopped taking on debt?

Yes. Household debt is significantly below pre crisis levels. At least in the US. Didn't check all of Europe.

-

I see things the way two cities is describing it. He has put it better than I can.

I do not see anything that says FFH has been wrong. My read is that the majority has yet to come to the same conclusion because we are so used to inflation. It takes time for societies to notice things have changed. But, when everyone finally notices and changes behaviour is when things can get interesting.

Well everyone basically changed behavior and deflation didn't happen. So what you're saying is that facts don't have much impact on you.

-

Please explain to me how the outlook is higher now than before? The US private sector has deleveraged quite a bit and you have a decent economic recovery under way?

If you have an economic shock that doesn't mean deflation. To achieve deflation you will need another shock probably of a higher than the one in 08. Just that fed may tighten a bit early doesn't mean automatic deflation. Those errors can also be reversed. If the economy slows down I think we can be pretty confident that you see QE4 coming in.

Given the facts it really doesn't seem like cheap insurance at all.

You say that 2008 relevant enough to draw conclusions from. Ok look long term and let me know what cases in history do you think are more pertinent to the present situation in the US. I would leave Japan out since their doesn't really look like the US.

Can you look in the rear-view mirror and point out what the second shock to Japan was that caused their two decade long deflationary trend?

I hate to get in the middle of other people's debates but I actually do think there is a fundamental difference between US & Japan, or a secondary shock if you prefer. It's demographcis. A shrinking population is a major impediment to economic growth. You could probably apply that to some European countries as well but the US has relatively good demographics due to immigration.

I was just replying when no free lunch posted. So I'll just build on his point. Yes in Japan you had a demographic problem. But also a horrible corporate culture and zombie banks. Also Japan is and was an export driven economy with perpetually poor domestic demand. Add to that a massive appreciation on the yen and new competition in export markets from China, Korea, and other players and you have a horrible situation.

Why the Japanese example is significant is that they broke through the zero barrier in inflation. However what the 08-09 example shows us is that Japan may have been the exception rather than the rule since countries like Spain which took much more economic pain than Japan didn't break the zero bound.

Also btw, I don't know why Japan is relevant here? Fairfax doesn't have Japanese deflation hedges and the Japanese economy is very different from the western economies on which Fairfax has deflation hedges

-

Wisdom,

Why are you referring to the globe since all the hedges are basically in the US and EU?

You also talk about a currency shock where the USD increases. The USD already increased a lot and inflation was steady. How much farther do you think the USD has to run? Also why will an increase in the USD deliver such a crushing blow to the US economy to put it in deflation when the US is a more local economy than most?

I've also looked at the FFH slides, they don't make a conclusive case that we are in imminent danger of deflation. Also the disinflation we saw in 2014 was a one time hit to CPI from commodity prices. Core inflation was steady. Btw, the negative CPI print we had in the US during the crisis was also commodity driven. Core inflation was not negative.

see http://data.bls.gov/timeseries/CUUR0000SA0L1E?output_view=pct_12mths

It would be nicer to create a credible economic argument (including the mechanisms) of how we're going to have an economic crisis of such a magnitude that would lead to deflation instead of just saying. Well USD shock.... deflation.

Also I don't see how the deflation hedges are anything like the mortgage CDS. With the deflation hedges you have the whole economic concept of sticky prices, a recovering economy with deleveraging going on, and a central bank that's committed to avoid deflation. With the CDS all you needed to make money was for already inflated house prices to stop rising.

-

Please explain to me how the outlook is higher now than before? The US private sector has deleveraged quite a bit and you have a decent economic recovery under way?

If you have an economic shock that doesn't mean deflation. To achieve deflation you will need another shock probably of a higher than the one in 08. Just that fed may tighten a bit early doesn't mean automatic deflation. Those errors can also be reversed. If the economy slows down I think we can be pretty confident that you see QE4 coming in.

Given the facts it really doesn't seem like cheap insurance at all.

You say that 2008 relevant enough to draw conclusions from. Ok look long term and let me know what cases in history do you think are more pertinent to the present situation in the US. I would leave Japan out since their doesn't really look like the US.

-

I am really confused by the conviction on this thread that we will have deflation. Why exactly would we have that? What kind of economic catastrophe would be required to achieve that and what is its probability?

The US has had only slight deflation for about a quarter at the depths of the 08 crisis. Spain only had just a slight drop in CPI in 08-09 after which CPI started growing again and that was with 25% unemployment. So why the high confidence in deflation?

-

Plus BRKs cash position is probably dragging it down. Part of that is solved now :).

I also don't know how these clowns get a WACC of 8.7%, I wonder what they are using for Ke and I'm pretty sure a) it's wrong and b) it's bullshit.

-

SD,

I am pretty busy right now, but don`t forget that the UAE has already soldiers on the ground around Aden since early August and the Saudis entered from the North late last week.

MORE IMPORTANT!!!

The lies from the EIA are finally being reported by themselves. They could no longer hide the truth that U.S. production had been declining more than their estimates found in their weekly reports. Rail car loads, inventories and State reports simply did not match. Their May and June production now being re-estimated are quite a bit lower than their latest August weekly figure!

That is why oil shot up just before noon.

Cardboard

Or it could be because of this:

-

Here's a little humour(?) from Gurufocus:

"As of today, Berkshire Hathaway Inc's weighted average cost Of capital is 8.68%. Berkshire Hathaway Inc's return on invested capital is 7.11%. Berkshire Hathaway Inc earns returns that do not match up to its cost of capital. It will destroy value as it grows."

Wow, these guys are smoking some pretty strong stuff.

-

I have learned so much from the man, it's hard to narrow it down to just one thing. But if I have to is this: Ignore the noise, think independently, and act boldly.

-

I don't really disagree with what you are saying here. My question is this: if we indeed get a shortage and prices go up to 6 or 7 what prevents these guys to take the rigs back out, do the whole drill baby drill thing, bump up supply and crash prices again?

-

Great points and I largely agree. A few minor quibbles:

As operating companies make a larger proportion of Berkshire compared to investments, the IV as measured by P/B multiple should creep up. But I think the P/B creep is very slow. If Berkshire fair value was say 1.5 P/B five years ago, it is probably 1.55 P/B now. So I think to a first approximation P/B is a pretty decent measure of estimating BRK's IV.

There are many different factors that are influencing P/B multiple

1. When Berkshire makes say investments in the stock market, those are worth pretty close to book value. They are worth a bit more than book value due to the strong possibility of beating the market, but again they face taxes on dividends which reduces some of the premium. If Berkshire consisted of nothing but $120 billion worth of stocks, then I do not think fair value would be anywhere as high as 1.5x Book value.

2. When Berkshire purchases operating companies, it typically pays a premium to the underlying companies book value and the total price paid becomes the new book value on Berkshire balance sheet. Sure they are worth more under Berkshire's umbrella but in aggregate, fair value for these would be closer to say 1.2x price paid or something around that.

PCP on which I think Berkshire got a particularly good deal is probably worth 1.3x at the high end to what Buffett paid for that company. But this is unusually attractive deal (much to my irritation as a PCP shareholder).

3. When Berkshire deploys capital internally say in BNSF or Energy or in any of its subs, that is where a larger premium of say something like P/B of 2 would be justified. So reinvested earnings are worth 2x book or maybe even higher. This is the part I disagree a bit with your comments. When BNSF increases its earnings by 10%, it is associated with a corresponding increase in equity or book value of BNSF. Othewise you are assuming that BNSF would have continuously increasing ROE - no growth in book value as earnings increase. While ROE might increase a bit, most of Berkshire's recent subs are likely to have a stable ROE, thus they would need growth in book value to increase earnings.

#1 and #2 pull P/B multiple down while #3 increases the multiple. So overall, if you do a point in time IV estimate and translate it into a P/B multiple, it is remarkably stable - although increasing by a very small amount each year.

There are a few other minor factors as well but for brevity let us ignore them.

Vinod

Vinod,

On point #1 I fully agree with you with shades of gray. That was kind of the point I was trying to make when I was talking about mark to market. I probably didn't express the point very well. Why BRKs market investments may be worth more than book is because they are leveraged with the float. But at this point the float is going into so many places that I would probably just mark the securities to market and leave it at that.

#2, and #3 I'll take them together. Yes the goodwill that BRK carries for the acquisitions shouldn't result in a large P/B attached to them. Especially in the near term. Now I'm going to get into a bit of murky conceptual valuation stuff so bear with me a bit.

The way I see it is that with certain big acquisitions: Mid-American, BNSF, and PCP Buffett actually acquired growth platforms. Companies which have a large opportunity set of projects that carry high rates of return by virtue of their economics or industry they are in. The kind of rates of return which are scarce outside of these companies. So instead of Buffett having to look for a stock to buy that will return 12% with the flip of a switch he can dump capital into MidAmerican and get 12%. This way he can reinvest the rivers of cash flowing into Omaha at high rates of return.

To see this change in strategy you can look at BRK investments up to the 2000s. They were mostly asset light companies that spit out a lot of cash. Coca Cola, P&G, Gillette, American Express. After 2000s you see asset heavy companies that can suck up a lot of cash: MidAmerican and BNSF. I think PCP will turn out to be some sort of roll-up like NOV was.

Now my question is. Since these growth platforms are acquired to reinvest Berkshire's cash at high rates of return for years into the future, and Berkshire is sure to make lots of cash in the future, when is the a lot of value actually created? When the cash is deployed or when the growth platform is acquired?

I'd love to hear your thoughts on this, especially since I may be getting a bit aggressive with mine. Thanks.

-

Right. Thanks for reminding me Jay. :)

-

Didn't they get that when they did the swap with ConocoPhillips a couple of years ago?

-

More WFC

-

I think he said somewhere in the article that he risked $100+ million to make that $34 million, crazy. Risking 100% of your capital to make 30% something percent.

Yea that could have easily went completely the other way and nobody would be writing stories then would they? Every time we have some big market dislocation, or large and sudden spike in volatility we hear about one of these guys. Does anyone remember any of the others from the past? Where are they now? They should be mega billionaires if they are so awesome.

Deflation hedges

in Fairfax Financial

Posted

I don't see how the deflation hedges protect you if rates go to 4%. If rates go to 4% you will have a good economy and positive inflation so you're not getting anything on the deflation hedges.